By leveraging technology, we can open new doors to scholarly inquiry for ourselves and our students. Through new collaborations, we can create exciting shared spaces, both virtual and physical, where that inquiry can take place. The library is a natural home for these technology-rich spaces.

Bryan Sinclair is associate dean, Public Services, at Georgia State University Library, where he is also project leader of CURVE: Collaborative University Research & Visualization Environment.

With origins in the digital humanities, digital scholarship in recent years has seen investigators from other disciplines — including the sciences and social sciences — embrace its tools and possibilities. New hybrid communities of inquiry are increasingly visual, collaborative, and spatial, or simply seek to make new connections possible in a digital world. Much of this is owed to advances and convergences in data visualization, mapping applications, and web development. Outstanding projects from the University of Richmond's Digital Scholarship Lab are forging new connections with history, geography, political science, sociology, and other fields through their Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States and Voting America portals. In public health, the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care is visualizing variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States today. In biology and ecology, digital initiatives — such as the Center for Conservation Biology Project Portal from the College of William and Mary and the Virginia Commonwealth University — are tracking regional concerns involving land use and bird species populations.

In the hands of talented scholars, teachers, and technologists, this form of scholarship can be liberating for both creator and user. Melanie Schlosser, Digital Publishing Librarian at Ohio State University Libraries, has defined digital scholarship as "research and teaching that is made possible by digital technologies, or that takes advantage of them to ask and answer questions in new ways."1 Edward Ayers uses the term generative in his definition to describe digital scholarship's function and effect. As generative scholarship, digital scholarship marks a move away from the passive, one-way form of communication from scholar to student or peer or novice. It is a new form of inquiry and practice that "generates new questions, new evidence, new conclusions, and new audiences as it is used." Digital scholars do not simply do this work and hand it to students to be quizzed upon. Rather, they say, "help us figure this out, help us make this better, help us make this richer" by working together.2 Because digital technologies are assumed in all that we will do in our increasingly visual and connected future, perhaps the most basic definition of digital scholarship is that it is and will be the scholarship of the 21st century.

This brings me to libraries, the shared spaces on each of our campuses that are ripe for transformation into incubators for digital scholarship. I propose that the 21st century academic library, perhaps more than any other unit on campus, is poised to support and promote that digital scholarship originating from multiple departments on campus, bringing them together in a central location. Unlike the digital humanities centers associated with history or English departments, Joan Lippincott has noted that a library's digital scholarship space (sometimes produced through a library and central IT partnership) can provide the neutral ground where all members are welcome.3 Although some retooling and shifting of resources may be required, the library has the added advantage of the facilities and personnel necessary to curate, describe, and preserve that scholarship and thereby make it continually viable and visible. Libraries have led the way in information access and sharing, from the development of machine readable cataloging (MARC) half a century ago to the metadata standards for the web used today. Libraries were among the earliest adopters and providers of Internet content, including digital archives and exhibits, research databases and discovery tools, and electronic books and journals — not to mention public-private partners on the Google Books Project that now benefits many of our campuses through the HathiTrust and benefits the public good through enhanced web searching. But perhaps the most significant contribution that academic libraries are providing today is our commitment to open access and new (a)venues for scholarly communication and data sharing. This contribution is evidenced by the explosion of institutional repositories from university libraries worldwide, in which librarians are making their campuses' unique digital assets available to their communities and beyond.4

Multiple Things to Multiple Users

The campus of the future will be increasingly connected and collaborative, and the library can be the community center and beta test kitchen for new forms of interdisciplinary inquiry. Libraries have always been in the business of knowledge creation and transfer, and the digital scholarship incubator within the library can serve as a natural extension of this essential function. In an age of visualization, analytics, big data, and new forms of online publishing, these central spaces can facilitate knowledge creation and transfer by connecting people, data, and technology in a shared collaborative space.

Big tech companies such as Google and smaller entrepreneurial start-up hubs (like the ones popping up in my own city of Atlanta) are encouraging "serendipitous interaction" through collective workspaces where ideas are generated and shared.5 The same is possible for the digital scholarship hub within the university library, where multiple users, groups, and disciplines can share the same space and digital canvases for collaboration. These spaces can also support "intergenerational exchanges" outside of the classroom between expert and novice, between experienced researcher and budding scholar. The undergraduate researcher should be not excluded from the mix, and can provide fresh generative ideas. Experts at the Scholarly Commons within the University of Illinois Library, for example, are actively engaging undergraduates and promoting their digital scholarship through regular blog posts and undergraduate research journals (figure 1).

Figure 1. The University of Illinois Library's Scholarly Commons supports scholarly work, including that of undergraduate researchers.

To have even broader impact, the library's digital scholarship incubator should support discovery big and small. On the large scale, it can bring together people investigating big research questions involving big data and content for extended study and analysis, which over time might result in monograph and journal publications or in dynamic new online projects and portals. But the incubator should also promote and celebrate those individual "bits" of discovery, those "eureka!" moments and everyday successes that contribute to scholarship's "long tail." The web and social media make it possible to share individual images, multimedia, maps, visualizations, simulations, mash-ups, and single ideas quickly to a wide audience — or even a very small one — which can in turn supply its own context and even add to the conversation.6 By applying good metadata (even for blog posts), as well as offering ongoing maintenance and permalinks, such contributions can be discoverable through Google and other popular search engines in the future. Whenever possible and appropriate, the library incubator should encourage open data and information sharing through Creative Commons licensing and open access (OA) repositories. In all of these ways, libraries can be seen as digital scholarship makerspaces.

Features of the Digital Scholarship Incubator

We have already begun to see shifts in personnel and resources to support new forms of 21st century scholarship in some libraries through the creation of digital scholarship centers,7 although this has been primarily the domain of larger research libraries. Each center's menu of services and resources can vary; it is natural for institutions to play to their individual programs, missions, and research interests. These centers might be called a "lab," "studio," or "commons," and the term "digital scholarship" — which can be ambiguous — might not even appear in the title (as in the "Scholarly Commons" example above). Also, because digital scholarship's technologies and possibilities are advancing so quickly, the tools and technologies provided are evolving and in flux. Following are some notable examples of "digital scholarship centers" in university libraries that illustrate the growing interest in supporting new forms of scholarship:

- Brown University — Digital Scholarship Lab

- Case Western Reserve University — Freeman Center for Digital Scholarship

- Columbia University — Center for Digital Research and Scholarship

- Emory University — Center for Digital Scholarship

- Georgia State University — CURVE: Collaborative University Research & Visualization Environment

- Rice University — Digital Scholarship Services

- University of Calgary — Visualization Studio

- University of Illinois — Scholarly Commons

- University of North Carolina at Charlotte — Digital Scholarship Lab

- University of Notre Dame — Center for Digital Scholarship

- University of Oregon — Digital Scholarship Center

In addition, North Carolina State University's inspiring new Hunt Library embodies many new services and technologies associated with 21st century inquiry, and the University of Washington Libraries has grouped its digital scholarship services and branded it as "ResearchWorks" (figure 2).

Figure 2. The University of Washington Libraries' ResearchWorks

At Georgia State University Library, where I have served as project leader for CURVE: Collaborative University Research & Visualization Environment for the past year, our focus groups and research have found some common trends, emphases, and areas for further exploration. Three of these broad areas of focus and expertise are increasingly vital for the library incubator to support and promote new forms of scholarship:

- Data services

- Visualization technologies

- Digitization, publishing, and sharing

Data Services

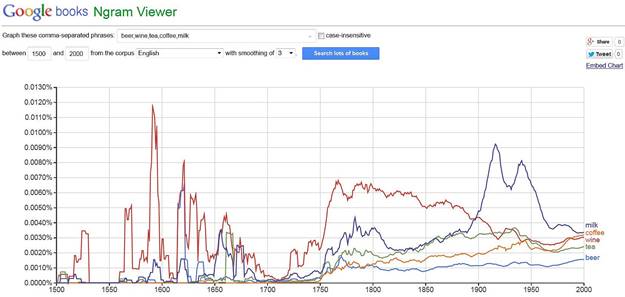

Access to specialized software and data sets, as well as the training and support services needed to use them, are essential for many forms of interdisciplinary digital scholarship. In addition to quantitative analysis software commonly used by researchers (including SPSS, STATA, and so on), there is growing interest in using both qualitative tools, such as NVivo and Dedoose for mixed-methods research, and visualization software, such as Tableau. With such a wealth of digitized texts at our fingertips — including much of our recorded history now available through Google Books (see figure 3) — there are new possibilities in the interdisciplinary field of text mining that might involve a wide range of scholars in the digital humanities, computer science, linguistics, statistics, and others. (For more information on text mining research, see the Center for Digital Scholarship at the University of Notre Dame's Hesburgh Libraries.)

Figure 3. A Google Books Ngram Viewer graph showing the occurrence of five beverage terms in digitized books from 1500–2000.

Digital scholarship's development appears to run in parallel with advances in data visualization, mapping applications, and geographic information systems (GIS). These technologies can give us a broader understanding of the world and our place in it. A picture might be worth a thousand words — and immeasurably more if a skilled web developer has digitized that picture with underlying data and interactive elements.8

According to Ayers, maps can allow us to visualize complexities and see all kinds of natural human phenomena. He and others often reference the "spatial turn" that is transforming many disciplines.9 Investigators at my own university have embraced maps and spatial data not just in geography and geosciences but also in history and literature as they seek to understand our past and human condition, and in areas of public health, policy studies, and criminal justice that seek to find workable solutions to today's challenges. Because students are now also requesting training and experience in using ESRI ArcGIS mapping software in other fields and disciplines, the library can be that central makerspace, incubator, and repository for spatial data. Established models for providing excellent numeric and spatial data services can be found at Duke University Libraries and New York University Libraries; these services have also been successfully integrated within the digital scholarship centers in libraries at Notre Dame, University of Illinois, and Case Western Reserve University.

Visualization Technologies

With advances in visualization software and tools comes the need for physical spaces designed for enhanced access to large-scale data visualization. Although this technology is often cost-prohibitive for most departmental labs and individual researchers, a few libraries now have this emerging technology, making it available to a broader base of teachers and scholars. Libraries at Brown University, Georgia State University, and North Carolina State University have implemented large-scale, high-resolution video displays designed for collaborative work. At Brown University Library's Digital Scholarship Lab, the centerpiece technology is a 16-by-7-foot video wall comprising twelve 55-inch high-resolution LED screens, ideal for analyzing a single object or text in greater detail or for viewing many images side-by-side for contrast and comparison. The overarching goal, according to Brown University Librarian Harriette Hemmasi, is "to support scholarly experimentation and ambition, helping faculty and students explore and define scholarly activities and forms beyond their current capabilities."10

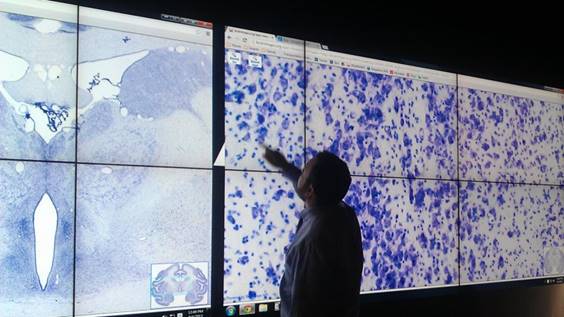

Large-scale displays designed for collaboration can change our perspective and reframe and amplify scholarship in shared physical spaces. Georgia State University Library's CURVE features a 24-by-4.5-foot high-resolution CURVE interactWall (figure 4) that adds touch capability for up-close interaction and engagement with the content. As with Brown's Digital Scholarship Lab, CURVE is not just about the hardware — it is equally focused on the people who use that hardware. Through a public-private partnership with a local technology company, we are hoping to explore enhanced human–computer and human–human interaction through natural user interfaces (touch and gesture-based) as well as the eventual incorporation of virtual reality technologies (such as Oculus Rift-type devices). Future developments in virtual reality will expand digital scholarship possibilities, allowing for increased communal, immersive, and experiential learning and discovery.

Figure 4. Exploring "inner spaces" using high-resolution brain maps on the CURVE InteractWall at Georgia State University

CURVE encourages the serendipitous interaction of various scholars and disciplines, with varying research abilities, coming together around shared technology. In addition to the large visualization wall, we have multiple group workstations with high-end computers (PC, Mac Pro, and Linux), professional graphics cards, a menu of specialized software, and additional large high-res displays, including a very large 84-inch, Ultra HD (4K) touchscreen (figure 5). Our CURVE planning documents and system specs are documented on the CURVE project site.

Figure 5. CURVE Interim Director Joseph Hurley at Georgia State explores the digital project "Planning Atlanta: A New City in the Making, 1930s–1990s" on the 84-inch Ultra HD (4K) touch display.

North Carolina State University's Hunt Library was built on the principles of enhanced collaboration, visualization, and interaction. Among Hunt's many spaces is the Teaching and Visualization Lab, which was designed as a "black box" theater for high-definition visualization and simulation, offering 270-degree immersive projection on three walls. On my initial visit to this facility, I was surprised by the social aspect of viewing visual data in such a large, shared space. It allowed for both an enhanced sense of collective investigation and a heightened sense of engagement with the content. Among the activities that Hunt Library supports are data visualization and simulation, gaming, interactive computing, programming, presenting, prototyping, making, modeling, and multimedia production. The Explore Hunt Library Technology page has more information about its emphases on research and learning and a list of technology and services.

Figure 6. The iPearl Immersion Theater at North Carolina State's Hunt Library

Digitization, Publishing, and Sharing

A digital scholarship incubator must also ensure that the content generated is accessible, sharable, and preserved. This includes analog materials that are being digitized and made available to a broader audience for the first time, as well as born-digital projects. The University of Oregon Libraries' Digital Scholarship Center offers consulting services for digitization and metadata, as well as training in these areas through regular workshops and seminars. Cornell University Library has developed its own Digital Consulting & Production Services (DCAPS) unit, which is "specializing in high-end digitization, metadata customization and creation, and online delivery mechanism development."

Sharing our unique content beyond the walls of the incubator is of critical importance. We can upload photographs, maps, audio files, journal articles, manuscripts, and more, and assign excellent metadata to them all, but it is that integrated portal or website that gives the collection its added context and meaning; as Ayers described it, it is this accessibility and utility that brings together multiple elements and generates "new questions, new evidence, new conclusions, and new audiences." Increasingly, we will need talented web developers to work alongside scholars, archivists, and librarians to help us build these dynamic and generative online portals.

Libraries concerned with digital scholarship are also reinventing traditional publishing and exploring new ways of hosting campus publications. Southern Spaces, a peer-reviewed, multimedia, open-access journal published in collaboration with the Robert W. Woodruff Library and the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, is an excellent example of what dynamic publishing can be, featuring articles with accompanying photo essays and images, short videos, and other embedded multimedia (figure 7).

Figure 7. The online journal Southern Spaces incorporates multimedia with text to present a fuller, richer story.

Librarians at the University of Washington Libraries are assisting authors and editors with both back-end workflow management, including facilitating author submissions and peer review processes, and front-end user experience, providing the web interface that lets users access current and archived content. Journals hosted by libraries allow for increased discoverability in Google and other search engines, detailed usage data and reports, and ongoing maintenance and content migration as technologies evolve. At Columbia University Libraries Center for Digital Research & Scholarship, personnel also assist with digitization of print back issues, copyright issues, and integration of interactive elements such as blogs and wikis.

Access, sharing, and preservation are no longer just about the published research findings. It is now an expectation and growing requirement that investigators manage and share their primary research data as well. Many libraries, including my own, are committed to working with investigators on managing their working data, writing data management plans for grants, and making their data accessible for future researchers through open data repositories.

Lastly, in the move from analog to digital scholarship, some libraries are increasingly supporting multimedia publishing and video and sound editing. The Freedman Center at Case Western's Library and the University of Calgary's Digital Media Commons offer many multimedia services designed to help faculty and student projects. Personnel are on hand to assist in the use of software, and they also provide workshops and tutorials.

Challenges and Final Thoughts

The technologies and possibilities described here are inspiring; my hope in this article was to avoid the more challenging issues surrounding personnel and funding, since there are no easy answers. Indeed, the question many of us face is not, "Where will the new funding and talent come from?" but rather, "How can we retool and reallocate our existing personnel and resources to create a 21st century digital scholarship and media center?"

As a starting point, professional development opportunities and incentives must be there for existing personnel to adopt new skills and talents, and we must clearly communicate expectations from the top if we intend the library to take on new services such as those offered by digital scholarship incubators. At my university, we rely extensively on bright student assistants, including undergraduate assistants (through our Honors College), graduate research assistants, and graduate students who receive a stipend through our newly launched Student Innovation Fellows Program. These budding scholars and peer mentors are often agile users of new technologies and are open to fresh ideas, and will be critical to the continued success of CURVE and future spaces like it. Working alongside them can inspire us all to embrace new approaches to scholarship, teaching, and our other work.

In the area of funding, the library can be seen as a centralized cost center that helps eliminate redundancies in the physical plant, hardware, and overhead spending. By combining campus resources, we can better facilitate team-based research from multiple areas in one centralized facility — one that might already be open 24 hours. At Georgia State, multiple units within the university have generously supported CURVE through one-time funding.11 The technology, services, and personnel we are committing to CURVE will be costly in the long run, and future streams of funding are uncertain. Grants, indirect cost recovery, corporate sponsorships, gifts, and public–private partnerships may all provide answers in both the short and long term; we are in ongoing discussions with our Development Office and vice president for Research & Economic Development to explore new opportunities. Student fees are another valuable resource that some libraries and central IT organizations can tap into, but we must never lose sight of the source of these funds as we provide services and technologies that benefit students and researchers at all levels.

Finally, to succeed, we cannot merely build these high-tech incubators in our libraries and expect scholars to come to us or understand their intrinsic importance. True, amazing technology and large, high-resolution displays like those at Brown's Digital Scholarship Lab, Georgia State's CURVE, and North Carolina State's Hunt Library might draw investigators involved with highly visual and collaborative research, but for the entire campus to understand the possibilities and transformative nature of digital scholarship, we must commit to increase our outreach and build new partnerships. Although the library incubator can be a catalyst, it is up to all of us — librarians, faculty, central IT staff, senior administrators, leading IT thinkers, alumni, and citizens, as well as our funding agencies and professional associations — to work together to encourage, promote, and support new forms of open scholarship over the more closed and insular forms of discourse from the past. What better way to demonstrate the exciting and important work being done on campus than by making our dynamic and generative scholarship available for others to see, use, and explore?

- Melanie Schlosser, "Defining Digital Scholarship," blog post, Digital Scholarship @ The Libraries, Ohio State University Libraries, March 11, 2013.

- Edward L. Ayers, "Discovery in a Digital World," video (36:00 mark), EDUCAUSE 2012 Annual Conference, November 9, 2012.

- Joan K. Lippincott, Harriette Hemmasi, and Vivian Lewis, "Trends in Digital Scholarship Centers," project briefing video (5:00 mark), Coalition Networked Information (CNI) Fall 2013 Membership Meeting, December 10, 2013.

- The Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR) currently lists more than 2,600 academic open access repositories worldwide, mostly operated by libraries and library consortia.

- Greg Lindsay, "Engineering Serendipity," New York Times, April 5, 2013.

- As one of many examples, Bernard K. Means and undergraduate students at Virginia Commonwealth University are using WordPress blogs to highlight their daily successes while 3D scanning artifacts for heritage and preservation at their Virtual Curation Museum.

- Lippincott, Hemmasi, and Lewis, "Trends in Digital Scholarship Centers," video (3:00 mark).

- For example, see our recent digital project, Planning Atlanta: A New City in the Making, 1930s-1990s, from Georgia State University Library. Funded by a recent NEH grant (Joseph Hurley, PI) the collection features digitized and georeferenced maps and aerial photographs that can be viewed as Google Maps and Google Earth overlays. Changing the transparency of the maps reveals the city's significant urban change.

- David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, eds., The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship, Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Lippincott, Hemmasi, and Lewis, "Trends in Digital Scholarship Centers," video (22:00 mark).

- At Georgia State, multiple units within the university have provided one-time funding for CURVE, including the Center for Instructional Innovation, Office of the Vice President for Research & Economic Development, Office of the Associate Provost for Strategic Initiatives & Innovation, and Information Systems & Technology (our central IT organization).

© 2014 Bryan Sinclair. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.