Key Takeaways

- A recent survey explored the strategies used by postsecondary students to gather information using Internet-capable cell phones, or smartphones.

- Notably, users of iPhone and Android devices are beginning to use new search input tools, such as spoken keywords, geographic location, camera images, and barcode or quick-response code scans.

- Most of the student respondents who conducted information searches on these devices understood the need to evaluate the reliability of what they found.

- Even though students claim they can read on their smartphones without being distracted, the evidence shows that disruptions did occur in homework sessions and during class time.

Keeping up with today's rapid technological changes reveals itself vividly in the changing ways people attempt to gather information. A survey conducted by the Weinberg Memorial Library at the University of Scranton analyzed the information retrieval strategies employed by a cohort of undergraduate students. The Scranton Smartphone Survey yielded some interesting results both in terms of technological advancement and reliance on traditional standards.

Two outcomes stand out:

- Those using the most user-friendly and interactive of the Internet-capable devices — the iPhone and Android — identified themselves as heralds of future behavior for the larger student body.

- In spite of the innovations, most students remain attuned to the need to evaluate the reliability of their sources.

Context

Each year since 2004, the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) has performed a national study of college students and their use of technology. The longitudinal information provided by the ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology is extremely valuable and frequently cited. However, it is not always possible for the study to address all aspects of the subject.

This is particularly true in the area of mobile technology, something the 2010 ECAR study acknowledged when it noted that Internet-capable cell phones have "fundamentally changed how students use technology."1 As such, educators have identified a need to learn more about how students operate these devices. Other surveys that complement ECAR's data include the Pew Internet and American Life Project's 2010 report Millennials, which covered mobile usage, text messaging, use while driving, and reliance on cell phones for communication.2 Several universities have studied mobile use from library-centric perspectives. Washington State University recently surveyed students, faculty, and university employees about patterns of handheld mobile device use, with a particular focus on the university's library catalog,3 while the California Digital Library surveyed students, staff, and faculty about their phone ownership, asking specifically about mobile service in libraries and in higher education.4 Similarly, in 2009 the Open University partnered with Cambridge University to survey staff and students "about their current use of mobile information services such as text alerts, use of SMS reference services … and use of the mobile Internet."5

These studies, among others,6 have begun to address the behavior students exhibit when using Internet-capable phones. An area yet to be explored is the extent to which students apply information literacy skills when using these devices. The 2000 Association of College & Research Libraries' (ACRL) Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education define information literacy as "a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information." It consists of core competencies that remain essentially constant regardless of the technology employed. As the practical implications of using information in the modern world keep changing, however, college students must adjust their information literacy skills to access it.

As smartphones become more ubiquitous, they increasingly influence the ways in which students search for, find, evaluate, and use information. Do current students exhibit information literate behavior when engaging with information on their phones? Do smartphones make it easier for students to demonstrate information literacy, or does this new technology perhaps erect barriers between students and effective searching for and use of information?

At the University of Scranton, current research on the relationship between smartphones and information literacy sought to answer these broad questions by building on the 2010 ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology. The Scranton Smartphone Survey focused on three critical areas of information literacy among students as defined by the ACRL Standards:

- Searching for information effectively

- Critical evaluation of information

- Incorporation of new information into one's knowledge base

Methodology

In fall 2010, I distributed an electronic survey on Internet-capable cell phone use via e-mail to a random sample of 832 University of Scranton undergraduates, all aged between 18 and 24 years of age. This sample represented 22 percent of the university's 3,781 undergraduate population in that age range. The survey consisted of 35 questions, most of them multiple-choice.7 As an incentive, all survey participants were entered into a prize drawing to win either an iPad or a $500 gift card for Best Buy or the Apple Store.

There was a 40 percent (333 students) response rate to the survey, of which 60 percent were female. General categories of academic majors at the university were proportionately represented (science, humanities, business, health, and education).

As in the ECAR study,8 student responses about their technology adoption were mapped to five categories, derived from the Rogers Innovation Adoption Curve. The majority of respondents (40 percent) identified themselves as Mainstream; but the Late Majority (29 percent), Early Adopter (17 percent), and Innovator (11 percent) categories were also well represented. Only two percent of the students self-identified as Laggards.

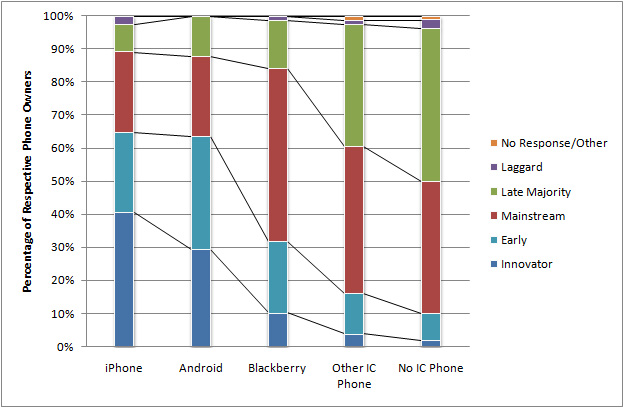

Phone Ownership

Of the respondents, 69 percent (229 students) reported owning an Internet-capable cell phone. This aligns with the national average of approximately 63 percent of the population as reported by the ECAR study. At the University of Scranton, 11 percent owned an iPhone, 12 percent owned an Android phone, and 20 percent owned a BlackBerry, with the remainder owning other phones such as the LG enV Touch or the Samsung Impression. For the sake of clarity, non-phone handheld devices like iPod touches or PDAs were excluded from the survey. iPads and other tablet computers were likewise excluded because few students on campus owned them at the time of the survey. Figure 1 shows percentages of Internet-capable (IC) phone ownership and self-categorization by the students who responded to the survey.

Figure 1. Phone Ownership and Self-Identified Adoption Categories

Perhaps not surprisingly, owners of iPhones and Android phones were much more likely to self-report a higher technology adoption level than owners of other phones — more than 60 percent of both iPhone- and Android-owning respondents classified themselves as either Innovators or Early Majority users. Just more than 30 percent of BlackBerry users and fewer than 20 percent of other Internet-capable cell phone owners reported the same.

With this important distinction in mind, iPhone- and Android-owning student behavior may serve as a potential predictor of the future behavior of the wider student body, as more undergraduates gain access to features currently only available to or convenient for iPhone and Android users. For this reason, the responses of Android- and iPhone-owning students will at times be singled out in this article.

The Academic Use of Internet-Capable Phones

In discussing the need for information literacy, the ACRL Standards refer to the "diverse, abundant information choices" that individuals face in "their academic studies, in the workplace, and in their personal lives." Information literacy is further described as "the basis for lifelong learning." Consequently, I chose not to limit questions about information seeking to those pertaining to academic pursuits; instead, I expected that information literate students using smartphones would demonstrate their skills in all aspects of information seeking, not just when engaged in coursework.

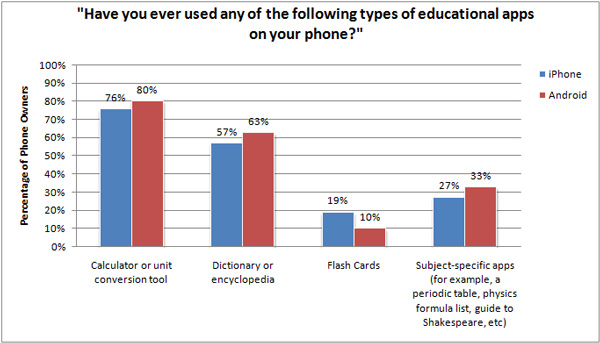

How do we respond to the frequently posed question, Do students use mobile phones for academic work? The 2009 ECAR study found just more than 11 percent of the respondents used their handheld devices for course activities while in class, but it did not ask whether these students used their phones for academic purposes outside of class.9 For this reason, the Scranton Smartphone Survey results countered the common perception that students think of their phones primarily for communication and entertainment and not for education. As such, it found several indications that student respondents would be interested in using their Internet-capable phones as academic resources if they were not doing so already (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Phone Owners Using Specific Academic Apps

First, more than 38 percent of students who owned Internet-capable phones reported accessing or trying to access the university's learning management system (Angel) via their phone, even though it was not mobile-friendly at the time of the survey. Also, more than 83 percent of these students specified that they wanted better mobile access to Angel, demonstrating a desire to interact with course materials via their phones.

Second, iPhone and Android owners reported using educational, academically related applications on their phones.10 Among iPhone users, 76 percent had used calculators or unit conversion tools, 57 percent had used dictionary or encyclopedia apps, 19 percent had used a flash card app, and 27 percent had used a subject-specific app (such as a periodic table app for chemistry). One of the flash card-using students commented:

"I can get 10 minutes of quality studying in anywhere I happen to be waiting for something."

Android users gave similar responses, though with more of a preference for subject-specific apps over flash cards. Some students noted that they also use productivity apps to make lists and calendars to help them organize coursework, while a handful of others mentioned word processors and document sharing tools.

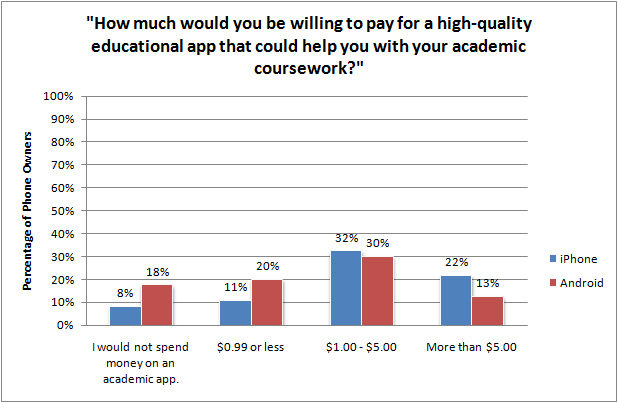

Furthermore, 54 percent of iPhone owners and 43 percent of Android owners were willing to spend more than one dollar on high-quality educational apps if they could help with their coursework (see Figure 3). One clarified:

"If it was specific to my major and helpful in what I was learning — yes."

Figure 3. Amount Phone Owners Would Pay for an Educational App

These factors suggest that students are, in fact, willing to invest in mobile learning tools specific to their academic needs. As a result, educators may have an opportunity to help students find and use educationally appropriate and helpful apps and mobile websites.

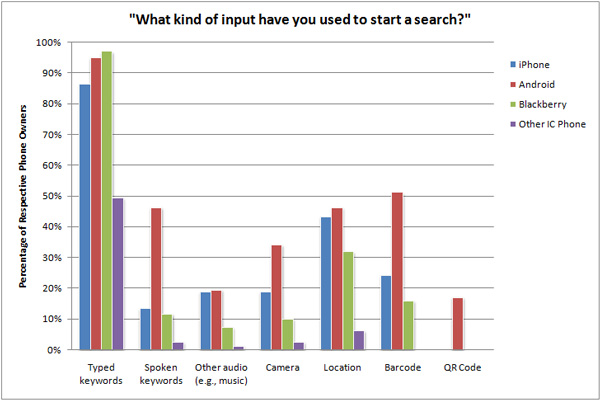

Searching for Information on an Internet-Capable Phone

Standard Two of the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education notes than an information literate student "accesses needed information effectively and efficiently." Many students clearly use Internet-capable cell phones to access information: of the student respondents who owned an iPhone, Android, or BlackBerry, almost all (98 percent) reported using their phones to search for information, though slightly fewer than half (49 percent) of their peers who owned other types of cell phones did.

How, then, does the use of a smartphone affect the likelihood of a student accessing information effectively and efficiently? The Scranton Smartphone Survey showed that owners of different types of phones search for information in different ways. While almost all Internet-capable cell phone–owning students used typed keywords, owners of iPhones and Androids appeared to use alternative input methods to find and access information. More than 40 percent of the respondents in this group have conducted a search using their geographic location. Such searches can be particularly important because "new possibilities emerge when a pupil starts learning with a mobile device with GPS functionality … a connection will be formed between the physical and virtual worlds in which the pupils find themselves."11 Additionally, a significant percentage of the Android-owning respondents reported using spoken keywords, images from their phone's camera, barcodes, and even quick response codes to search for information. Figure 4 shows the percentage of survey respondents who used specific methods for beginning a search, with multiple types possible.

Figure 4. Percentage of Students Using Different Inputs to Start a Search

While the ECAR study noted that "it is not clear … how many college- or education-related tasks are being done" as part of these searches,12 the results of this study would seem to suggest that — if iPhone and Android users can indeed serve as predictors of future student behavior — universities should expect to see more students move beyond text-based searching in their information-seeking processes. Educators, then, should be aware of the search capabilities available to students and incorporate them into both information literacy instruction and campus information dissemination rubrics when possible and appropriate.

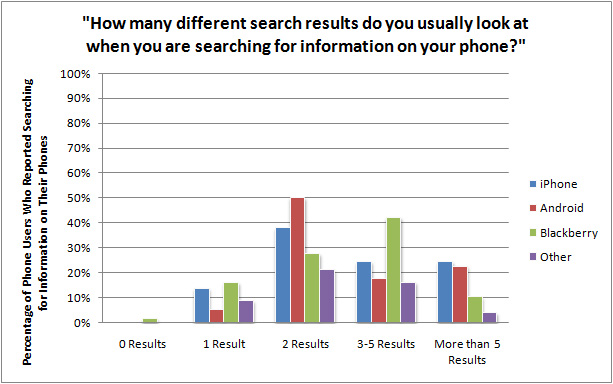

However, the increased use of alternative search input methods does not necessarily mean that student searches will be more comprehensive. ACRL's Standard Two specifies that an information literate student "assesses the quantity, quality, and relevance of the search results." In 2009, Art Taylor suggested that such behavior would be unlikely because information for students "is just another commodity that is consumed at the lowest cost. The cost, in this context, is effort, and the Gen M seeking information often perceives the lowest cost as the most convenient, readily available information with limited consideration for quality."13 The survey results seem to confirm Taylor's suspicion. Most of the respondents who reported searching for information on their phones said that they only reviewed one or two of those search results. Even among the Android and iPhone users (who were the most likely to review additional search results), fewer than 25 percent reported looking at more than five of their initial search results (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage of Phone Users Looking at Different Search Results

These results suggest that students have high expectations of search engines; they expect to find answers quickly and easily, without sorting through numerous pages of query results (or as Lorcan Dempsey expressed it, they have a "need to get to relevance quickly"14). Another factor to consider is what a 2010 study by Eszter Hargittai et al. found: that is, "evidence of users' trust in search engines with respect to the credibility of information they find when using these services." The authors noted that students "chose a Website because the search engine had returned that site as the first result suggesting considerable trust in these services."15 Be that as it may, educational search tools like library catalogs will increasingly be ignored by students should they not meet these expectations in the mobile environment.

Evaluation of Information on an Internet-Capable Phone

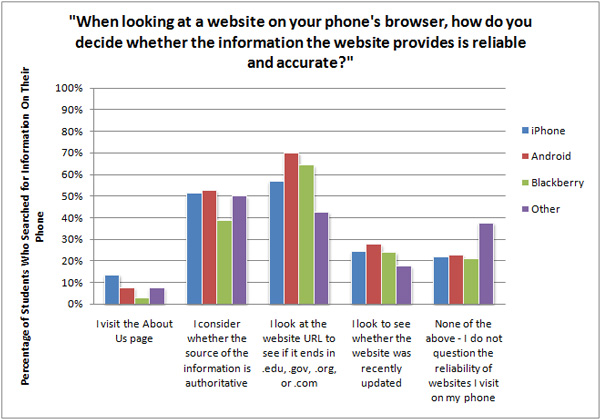

ACRL Standard Three states than an information-literate student "evaluates information and its sources critically." According to the Scranton Smartphone Survey, the majority of student respondents who searched for information on their Internet-capable cell phones used a basic evaluation method (such as considering the source) before accepting the information they found as authoritative. While two students noted that they tended to go to previously used and trusted sites on their phones and another two mentioned that they compared information across search results, a significant number (25 percent) claimed that they did not question the reliability of sites they visited on their phones. One student commented:

"What I search for on my phone isn't very important."

Fewer than 10 percent of the students who searched for information on their phones reported visiting a website's "About Us" page, an evaluation method commonly used when viewing websites on laptop or desktop computers. This is likely due to the fact that the student would have to load an additional web page onto their phone, which could be a time-consuming process depending on the speed of the their data connection. Figure 6 shows the percentage of students who used various approaches to determining whether websites found on their phone's browser provide reliable, accurate information.

Figure 6. Methods of Determining Validity of Website Information

Notably, even though students reported that they evaluated information, this process was not necessarily complete or thorough. In 2010, Hargittai et al. found that of study participants who "made remarks about either a site's author or that author's credentials, … none actually followed through by verifying either the identification or the qualifications of the authors."16 To determine the extent to which students properly evaluate information found on their phones, observation of them at work must to be conducted in future research.

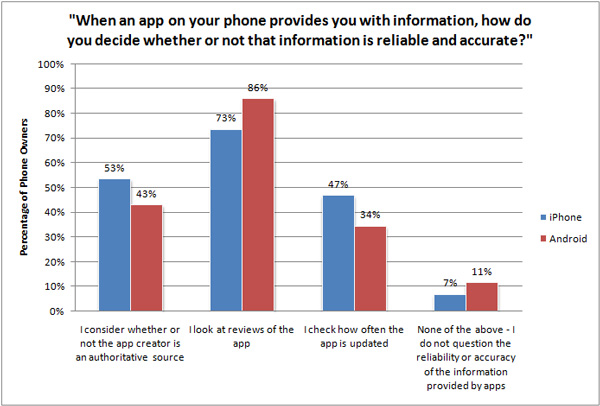

Interestingly, those who used third-party apps on their phones seemed more likely to use some method of evaluation to consider the reliability of information they found. Many student respondents (73 percent of iPhone owners and 86 percent of Android users) used app reviews to judge an app's reliability. Fewer than 7 percent of iPhone users and approximately 11 percent of Android users said they would not question the reliability of an app (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Methods of Determining Reliability of App-Provided Information

Two students noted in comments that they "fact check" information found through an app by "looking it up in the web browser" or running it through a search engine, believing that step would add "reliability and accuracy." This response echoes that of the 2008 CIBER Report, which suggested that "users assess authority and trust [of online websites] for themselves in a matter of seconds by dipping and cross-checking across different sites and by relying on favoured brands (e.g., Google)."17 Ultimately, though, these two comments indicate that these students struggle with Standard One of the ACRL Standards by misunderstanding how information is "produced, organized, and disseminated."

For both apps and mobile web access, students seemed to be conducting their evaluations "on the fly," at the time of information access. These results further indicate that educators must reinforce with students the importance of evaluating the reliability, validity, accuracy, authority, timeliness, and potential bias of information, regardless of whether the information is accessed via a mobile website or a native app, or whether via a mobile device or a laptop or desktop computer. As Marguerite Koole wrote, "teachers or experts [can] help learners understand how to navigate through knowledge in order to select, manipulate, and apply already existing information for unique situations."18

Converting Information into Knowledge on Internet-Capable Phones

Standard Three of the ACRL Standards also discusses the conversion of information into knowledge: an information literate student "incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system." Koole wrote about the interaction between a mobile device and a learner, noting that the characteristics of mobile devices can affect "cognitive load, the ability to access information, and the ability to physically move from different physical and virtual locations."19 In fact, "effective mobile learning … results from the integration of the device, learner and social aspects."20

Many educators have questioned the role of mobile devices in this crucial area of knowledge building, worrying that phones might inhibit a student's understanding of information. One learning outcome of ACRL's Standard Three states that an information literate student "reads the text and selects main idea." Even this basic aspect of information literacy has some educators concerned about its application in the mobile environment. For example, the 2008 University College London CIBER report speculated that users would not truly "read" online, let alone on a small-screened mobile device:

"The average times that users spend on e-book and e-journal sites are very short: typically four and eight minutes respectively. It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense, indeed there are signs that new forms of 'reading' are emerging as users 'power browse' horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins."21

Students participating in the Scranton Smartphone Survey were asked whether they had read a multi-paragraph text such as an article or a book on their phone; slightly more than half of the respondents reported having done so. They listed convenience and portability as their primary reasons for reading on their phones. For example, one student noted:

"My phone is always on me. I can easily read from a phone while I walk, or eat in a public place like the cafeteria."

Certainly, though, students are not doing all of their reading on phones. Several students mentioned that they read on their phone only when a computer was not readily at hand. "I was away from my computer and didn't want to wait," explained one respondent.

Beyond the activity of reading, other education literature and reports such as the Mobile Difference report of 2009 have expressed concerns that the "continual information exchange" taking place in the mobile world could cause "'serial digital distraction' as people respond to a slew of bits cascading to them."22 The Scranton survey addressed one aspect of these concerns when it questioned whether or not Internet-capable phones serve as distractions in the learning process. When asked if they were able to focus their attention while reading on their phones, a surprisingly high 92 percent of the respondents said "yes," while only 3 percent said "no." This could perhaps result from use of well-designed phones, as Koole suggested: "Learners equipped with well-designed mobile devices should be able to focus on cognitive tasks … rather than on the devices themselves."23

However, students did report that their phones were distracting in other ways. Of Internet-capable phone-owning students, 81 percent said that their phone distracted them either "sometimes" or "frequently" during homework sessions outside of class. A much lower but still significant 43 percent said that their phones distracted them either "sometimes" or "frequently" during class. These results parallel research at DePaul University that "showed that mobile computing along with internet access has caused distractions for students."24

Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of the Scranton Smartphone Survey indicate that, while students are interested in using their phones for academic purposes, they still require guidance from educators to choose the most appropriate mobile resource and to evaluate mobile websites and mobile apps. As a single-site survey, however, this research was limited in scope — and in many ways has resulted in more questions than answers. Further investigation using focus groups or observational research to gain deeper insights into student search processes would be helpful.

A study analyzing student search behavior across smartphones, tablet computers, and laptop or desktop computers, for instance, would be valuable. As Agnes Kukulska-Hulme noted, "Learners tend to move between using desktop computers and mobile devices, and maybe touch-screen displays in public areas, often for different parts of a learning task."25 The information literacy world would benefit from a closer parsing of when and why users switch between devices.

The existing data nonetheless permit a few generalizations and recommendations:

- Information literacy instructors should become familiar with new search methods (such as quick response codes) to help students use them effectively and efficiently.

- Students should be encouraged to review a range of search results, particularly when searching for academic information.

- Information literacy instructors should help students understand how to evaluate information, especially when it is presented in a nontraditional form, such as a native app.

- Students may need assistance from educators in applying information literacy skills they have learned while searching on a laptop or desktop to the mobile environment.

Overall, the Scranton Smartphone Survey provides a starting point for future research on student use of Internet-capable phones. I will continue my research here at the University of Scranton but also encourage others to conduct similar studies on their own campuses. Interested researchers may contact me at [email protected] for a copy of the survey instrument.

- Shannon D. Smith and Judith Borreson Caruso, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010 (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2010), p. 21.

- Paul Taylor and Scott Keeter, eds., Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next (Washington, DC: Pew Research Group, 2010).

- Joel Cummings, Alex Merrill, and Steve Borrelli, "The Use of Handheld Mobile Devices: Their Impact and Implications for Library Services," Library Hi Tech, vol. 28, no. 1 (2010), pp. 22–40.

- Rachael Hu and Alison Meier, Mobile Strategy Report: Mobile Device User Research (Oakland, CA: California Digital Library, 2010).

- Keren Mills, M-Libraries: Information Use on the Move: A Report from the Arcadia Programme (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Arcadia Programme, 2009).

- See also: Victoria Owen, "Library and Student Support (L&SS): Flexible, Blended, and Technology-Enhanced Learning," inMohammed Ally and Gill Needham, eds., M-Libraries 2: A Virtual Library in Everyone's Pocket, pp. 215–218 (London: Facet Publishing, 2010); Ryerson University Library, Mobile Device Survey 2009 (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2009); Agnes Kukulska-Hulme and John Pettit, "Practitioners as Innovators: Emergent Practice in Personal Mobile Teaching, Learning, Work, and Leisure," in Mobile Learning: Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training, Mohamed Ally, ed. (Edmonton, AB: AU Press, 2009),pp. 135–155; and Wendy Starkweather and Eva Stowers, "Smartphones: A Potential Discovery Tool," Information Technology and Libraries, vol. 28, no. 4 (2009), pp. 187–188.

- I was advised not to include more than a few open-ended questions in order to achieve a higher response rate to the survey.

- Smith and Caruso, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010, p. 8.

- Shannon Smith, Gail Salaway, and Judith B. Caruso, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2009 (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2009), pp. 97–98. The survey did ask what institutional information technology services students would "most likely use" from their mobile device if it were available. Notably, learning management systems ranked third, behind e-mail and student administrative services like grades and registration.

- While some BlackBerry and other Internet-capable phone owners indicated that they did use third-party apps, their numbers were so few as to be unrepresentative. Therefore, whenever apps are discussed in this article, only iPhone and Android owners are considered.

- Menno Smidts, Rinske Hordijk, and Jantina Huizenga, The World as a Learning Environment: Playful and Creative Use of GPS and Mobile Technology in Education (Utrecht: SURFnet/Zoetermeer: Stichting Kennisnet/Amsterdam: Creative Learning Lab/Amsterdam: Instituut voor de Lerarenopleiding van de UvA, 2009), p. 4.

- Smith and Caruso, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010, p. 22.

- Art Taylor, "Gen M and the Information Search Process," in Teaching Generation M: A Handbook for Librarians and Educators, Vibitana Bowman Cvetkovic and Robert J. Lackie, eds. (New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, 2009), p. 72.

- Lorcan Dempsey, "Always On: Libraries in a World of Permanent Connectivity," in M-Libraries: Libraries on the Move to Provide Virtual Access, Gill Needham and Mohammed Ally, eds. (London: Facet Publishing, 2008), p. xxvi.

- Eszter Hargittai, Lindsay Fullerton, Ericka Menchen-Trevino, and Kristin Yates Thomas, "Trust Online: Young Adults' Evaluation of Web Content," International Journal of Communication, vol. 4 (2010), pp. 468–494.

- Ibid., p. 480.

- University College London (UCL) CIBER Group,Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future, CIBER Briefing paper, no. 9 (London: UCL, 2008).

- Marguerite Koole, "A Model for Framing Mobile Learning," in Mohamed Ally, ed., Mobile Learning: Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training, p. 41 (Edmonton, AB: AU Press, 2009).

- Ibid., p. 32.

- Ibid., p. 38.

- UCL CIBER Group, Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future, p. 10.

- John Horrigan, The Mobile Difference, Pew Internet and American Life Project (2009), p. 97.

- Koole, "A Model for Framing Mobile Learning," p. 29.

- Mark Hawkes and Claver Hategekimana, "Impacts of Mobile Computing on Student Learning in the University: A Comparison of Course Assessment Data," Journal of Educational Technology Systems, vol. 38, no. 1 (2009–2010), pp. 63–74.

- Agnes Kukulska-Hulme, "Will Mobile Learning Change Language Learning?" ReCALL, vol. 21, no. 2 (2009), p. 159.

© 2011 Kristen Yarmey. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.