Key Takeaways

- Traditional technology assessment — whether bottom-up or top-down — rarely matches the speed of technology adoption in campus teaching and learning environments; the result is often an IT infrastructure out of sync with campus practices.

- Rapid Assessment of Information Technologies (RAIT) offers a more balanced approach to technology evaluation, allowing universities to quickly identify, evaluate, and recommend new education technologies.

- RAIT centers on small, semester-long use cases that let researchers gather data about a technology's benefits and limitations.

- The process follows a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board that employs qualitative and quantitative research methods and results in broadly disseminated outcomes, best practices, and support tools.

At the University of Colorado, Boulder, Caroline Sinkinson is teaching and learning librarian, University Libraries; Mark Werner is associate director of Academic Technology Strategy and Support; and Diane Sieber is associate dean for Education, College of Engineering and Applied Science.

The rapid pace of technological change has become the norm in modern digital and information landscapes. Most operating systems, including both Microsoft and Mac OS, change every year or two; mobile devices develop annually with increasing sophistication; and new social- and cloud-based software appear and disappear almost daily. Within educational contexts, the pressure of such changes is felt acutely by educators, administrators, and learners alike.

Enthusiasts proclaim that emerging hardware and software technologies will replace closed systems — such as the LMS — and modernize technology-assisted pedagogy.1 Simultaneously, skeptics warn against framing emerging technologies as an inevitable improvement or a guaranteed solution in any context.2 Despite the unresolved debates, teachers and learners continue to struggle to keep pace with changes to their devices and hardware, and they remain overwhelmed by the abundance of new technologies and their proclaimed utility to learning. The attention devoted to frequent re-adaptation, learning new tools, and adjusting work tasks accordingly can be significant and disruptive. These disruptions impact educators and administrators in institutions of learning around the world.

In the United States, recognition of this educational dilemma is evidenced in policy documents such as the US Department of Education's National Education Technology Plan. In 2010, US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan called on educators to apply advanced technologies "to improve student learning, accelerate and scale up the adoption of effective practices, and use of data and information" to leverage technology in support of "continuous lifelong learning."3 Inevitably, graduates will find themselves in complex information and technology environments whether in workplace, civic, or social contexts. In the workplace, for example, graduates will be expected to navigate varied streams of information and to analyze, synthesize, and identify patterns therein.4 Fluency and experience with modern information technologies are central to meeting this demand. Institutions of higher education have an obligation to support students' development of digital and information literacies.

Supporting widespread faculty adoption of emerging technologies in the classroom entails many obstacles for institutions. A 2008 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development report identified three core barriers to adopting technologies when teaching:

- The absence of appropriate incentives for technology use and innovation adoption

- The teaching profession's dominant culture, which too often ignores research-based evidence on good teaching methodologies and strategies

- Teachers who lack personal experience with and a vision of what technology-enhanced teaching might look like5

Other studies identify other teaching barriers, including lack of time, desire for reward, low technology confidence, and priority of research.6 In response, universities seek solutions such as communities of practice, teaching and learning centers, or monetary incentives. Although one solution might not fit all institutions, it is widely accepted that:

Though faculty members' needs and constraints vary, faculty support is increasingly necessary in an age of technological advancement that brings new educational tools that faculty members are being asked to learn about and use in their classrooms.7

Central IT units also need information that will let them evaluate the risks (security, privacy, failure) and costs (licensing, hosting, and human resources) associated with purchasing and supporting a new technology. They need some sense of a technology's demand and whether the campus as a whole would endorse its adoption. They also must consider how the technology interacts within the larger IT structure on campus. All this occurs as IT professionals confront pressures from leading technology adopters and other stakeholders to quickly assess, explore, and support new technologies with rich teaching and learning affordances.

To address these challenges, we present here the Rapid Assessment of Information Technologies (RAIT) approach, a collaborative and multidisciplinary process for quickly identifying, evaluating, and recommending new academic technologies for adoption. We also describe our early attempts at applying this process to exam social learning tools.

Models of Technology Evaluation and Adoption

In their article, "Middle-Out Approaches to Reform of University Teaching and Learning," Rick Cummings and his colleagues evaluate methods of change management within institutions of higher education.8 They identify top-down and bottom-up approaches to change management as the norm at most institutions and conclude that a middle-out approach facilitates the greatest impact on technology integration to improve teaching and learning. In this middle-out approach, middle managers and practitioners, rather than senior-level managers, worked collaboratively and "through a combination of personal inspiration and policy based on emergent practice, changed the university environment sufficiently to force both high-level policy change and change in practice among teaching staff."9 Given the challenges confronting higher education, the middle-out approach is ideal for confronting problem-oriented questions and investigations.

On our campus, we have observed many of the trends that Cummings and his colleagues report. Several engaged faculty members explore and apply technologies to their teaching in very innovative ways; such investigations sometimes grow organically, are shared with other colleagues, and establish best practices, demonstrating a bottom-up approach. Despite these successes, even the most innovative early adopters have expressed anxiety about maintaining high levels of change throughout their careers due to the time and effort needed to identify, evaluate, apply, and assess the potential benefits of technological and pedagogical innovations. More often than not, faculty members engage in innovation based on internal motivations without institutional incentives or support. The value that such faculty members provide is immense and will continue to be essential. However, given the pace of change in higher education and technological advancements, relying solely on bottom-up methods of innovation will not adequately support teaching and learning goals. Furthermore, individual faculty-driven change can create inefficiencies in licensing costs, support, and scaled storage and server capacity, as well as an uneven user experience as students migrate through departments and encounter differing versions of similar technologies.

In addition to supporting innovative teachers, our institution leads the adoption of centralized educational technologies and tools. Directed by senior-level managers and focused on strategic goals, funding, and infrastructure, tools and technologies are often selected based on their perceived application across disciplines and schools. Historically, the choice has been a one-size-fits-all, vendor-driven solution. In specific situations, such tools can suffer under-use because they either provide more functions than are needed or don't quite meet teacher and learner needs. Additionally, given the university structure and the governance therein — which tend to dampen innovation's pace — it is not surprising that technology changes do not occur as rapidly as necessary.

Neither of these traditional methods of planning, offering, and supporting innovation is responsive or rapid enough to manage the challenges facing teachers and learners today. Given only these two approaches — teacher-led or centrally directed innovation — institutions are at risk of creating an expensive and disjointed technology landscape in which the IT infrastructure and support are not in harmony with the teaching and learning activities on campus.

To address these shortcomings, we offer an additional strategy that echoes the middle-out process. RAIT supports collaborative efforts to identify relevant and pressing questions, gather early adopters, and — through analysis and study — offer evidence that can impact broader adoption and institutional directions.

Rapid Assessment of Information Technology Model

In spring 2011, we formed a research team focused on providing our central IT unit with information about the teaching affordances of, and support needs for, the GoingOn academic social network. Our success with that study led us to expand our inquiry to another social network, including Google Apps for Education, and to develop a process — RAIT — that would provide enough research rigor to be valuable to scholars of teaching and learning, yet quick enough to provide information to the central IT group, and specific enough to guide local faculty in their choices of learning technologies.

Real-World RAIT: Social Network Research

As we searched for an educational technology that extended beyond the affordances of the local LMS, we engaged in our first RAIT study. Faculty and students consistently articulated interest in tools that encouraged participation, sharing, collaboration, and knowledge building similar to authentic online communities. Therefore, we began investigating social network technologies and solutions.

The Pilot Studies

Our 2011 pilot of the GoingOn social network included seven communities: four classes from both the sciences and the humanities, as well as three communities, including the Graduate School, a campus committee, and a research group. Each course or community employed the tool for targeted purposes and specific needs during one semester. During participants' use, the RAIT team compiled feedback through surveys, interviews, and observations. Based on this experience, we recommended that our university continue searching for a social networking solution.

In spring 2012, we studied the use of Google Apps for Education (GAFE), observing four courses using GAFE: two engineering courses, one education course, and one architecture and planning course. We then surveyed students and interviewed students and faculty members in those courses.

Study Results

Through our GAFE and GoingOn social network studies, we discovered a campus need for teaching and learning tools beyond those in a learning management system (LMS).

Although faculty and students valued the campus LMS for managing course artifacts and teacher-to-student communications, courses emphasizing social, collaborative, or problem-based learning often require more flexible tools. Also, courses that emphasize authentic learning experiences or student exposure to communities-of-practice need tools that extend beyond the university community.

Generally, students reported positive attitudes toward both of the social networking technologies we studied. However, student satisfaction clearly increased when teachers clarified the tool's learning purpose and its reason for use. When a tool was seen as a distraction and not explicitly tied to learning, students were less engaged.

Similarly, students valued credit-based incentives for actively participating in the online class environment. Many students reported that this and active teacher communication equalized their concerns about peer participation while also increasing the sense of a course community.

Recommendations

Based on the results of our pilot studies, we recommended deployment of GAFE on the CU Boulder campus.

We found that GoingOn had some attractive social networking features, including a wiki and blog (with media attachments), sharing across communities, and a compelling drag-and-drop interface with modular widgets for arranging a community. However, GoingOn had yet to become a stable platform, and the company had yet to mature to the level of an enterprise service provider. Ultimately, the company went out of business.

Multidisciplinary Team

Because our goal is to establish a team that moves across disciplinary boundaries, the multidisciplinary make-up of team members is essential. Our research team includes a faculty member and associate dean, a campus-level IT, and a faculty member in the University Libraries.

This defining characteristic of multi-discipline membership allows investigations to cross boundaries. In our case, individual team members were able to reach out to their specific communities, engage constituents in dialogue about needs, recruit and involve innovative early adopters of technology, and widely distribute our study's findings and results.

Teaching and Learning Focus

Our inquiries focus on emerging technologies in educational contexts for two central reasons:

- The technologies have the potential to support collaborative, participatory, and open pedagogies.

- Learners are immersed in technologically complex knowledge environments in both formal and informal learning contexts.

Institutions of higher education have an obligation to nurture students' 21st century and digital literacies. Innovative technology use in the classroom models technological proficiencies and provides an environment in which students can practice digital literacies. Our investigations are driven by these goals, rather than by a simply techno-centric vision. Indeed, we ascribe to Punya Mishra and Matthew Koehler's model of technology integration in learning, which argues for the "thoughtful interweaving of all three key sources of knowledge: technology, pedagogy, and content."10

Process Overview

We focus on small, semester-long pilot use cases and gather affordance data and unexpected user exploits through a research process approved by the Institutional Review Board. We then broadly disseminate outcomes, best practices, and support tools while alerting central IT to emerging academic technology tools.

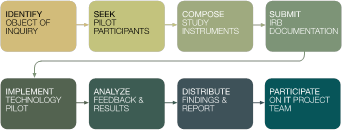

We time our projects to provide quick practical outcomes that inform future decision making and wider adoption. As figure 1 shows, our process of inquiry follows seven main steps:

- Identify the object of inquiry

- Seek pilot participants

- Compose instruments

- Submit Institutional Review Board documentation

- Implement pilot

- Analyze results

- Distribute the report to stakeholders

If the technology is to be adopted campus-wide, we add an eighth step: assemble a project team to represent the views of faculty and students as stakeholders in the project.

Figure 1. The RAIT process (the final step applies only for

campus-wide adoption)

Goals

In each pilot study, we ask one central research question: "Does X provide a relative advantage over the functions available from other campus or openly available tools?" In pursuing this central question, we have three goals:

- Identify the affordances and limitations technologies have for certain types of teaching and learning

- Identify the teaching and learning methods that work best with certain technologies

- Assess whether teaching with the technology was effective

Methods

We designed a mixture of qualitative and quantitative instruments that allow emergent themes and observations to surface. Semi-structured interviews and observations let us "observe and interpret meaning in context," while surveys offer us a broader set of data on student and faculty perceptions.11

The survey instrument collects basic demographic details such as rank, field of affiliation, and self-described technological proficiency. Next, the survey seeks to gather participants' attitudes toward educational technologies in general, as well as participants' satisfaction in terms of usability, technical functions, and ease of use. In addition to the survey information, we extend invitations for interview and focus group participation to all faculty and students. The final component of our data gathering involves periodic observations of the technology and participants using it. During these observations, we note the types of features most heavily used and what type of communications are underway.

Results

In each of our investigations, we used the same process and instruments, with minor revisions tailored to the particular technology. This let us begin to construct a broad view of teaching and learning experiences with various social technologies.

Following each study, we compile specific cases or applications directed at specific teaching and learning objectives. We intend to continue to build this body of knowledge with the intention of identifying "constructs that would apply across diverse cases and examples of practice."12 In effect, we are simultaneously generating documentation and best practices that might be applied to similar needs and tools, while also looking to answer broader questions:

- What motivates faculty members' use of social and emerging technologies in teaching and research?

- Are there patterns in faculty members' assessment of tools?

- What barriers exist for faculty members?

- What would assist faculty members in surmounting barriers?

- What benefits or drawbacks to the tools do students perceive?

- Are there patterns in student assessments of tools?

- What barriers exist for students?

- What would assist students in surmounting barriers?

Over the course of our studies, faculty and students have consistently expressed the need to

- engage in conversation at distances between learners, teachers, experts, and the community;

- enhance collaborative content creation;

- facilitate collaborative content curation and sharing; and

- manage and provide a central hub for the course.

Reporting

After conducting the study and compiling our data, we produce reports and disseminate them widely across the campus to a variety of stakeholders. Each report includes a summary and recommendations, a thorough description of the tool, identified affordances for teaching and learning, use case descriptions, and issues encountered during the pilot. Often, we follow the written report with in-depth conversations about future implementation or adoption; we have found that such additional conversations are helpful. In one instance, our findings directly drove the decision to discontinue a tool's use; in another instance, the findings led to a tool's campus-wide adoption and use. In addition, once a tool is adopted, faculty-to-faculty presentations on best practices with it furthers the dissemination.

Our study's small, pilot nature offers only a partial look into deep relationships between tools and learning outcomes. Therefore, we typically conclude reports with suggestions for more robust research studies. Our snapshot studies identify local needs and characteristics, which, when coupled with broader studies such as those generated by the EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, the Babson Group, or New Media Consortium Horizon Reports, provide a great deal of information and evidence that powerfully informs decision making. Our goal is to increase the likelihood that our decisions make us the best stewards of university funds and increase the likelihood that our faculty colleagues will use technologies that can improve their teaching effectiveness.

Risks

The RAIT research approach holds a few risks, including tensions between rigorous research and applied studies, between rapid assessment and deliberative decision making, and between vendor and researcher aims.

Research vs. Applied Studies

First, although most research universities privilege research, administrative units don't necessarily value research as inputs to their daily work. Also, widespread faculty agreement about what constitutes research may not exist. So, while the research rigor of this process appeals to some academics on campus, others might dismiss the methodology because it concludes rapidly and focuses on application.

To address this, research teams must clarify to local stakeholders that their initial goal is to establish a rich descriptive record about a specific emerging technology. The second goal is to build local knowledge that might contribute to broader research findings and extended research.

Recently, for example, we participated in a more robust project in which EDUCAUSE and Internet2 sponsored research into electronic texts. This work combined many small case examples of e-text use in 393 college classes at 23 sites across the US. The study treated our campus case study as one example and let us make inferences and recommendations locally; at the same time, we benefitted from 22 other similar case examples from around the United States that revealed patterns about e-text's potential as a teaching and learning tool.

Further, while the RAIT process is valuable for the central IT unit as an early alert on emerging technologies, that unit might not understand how the research model fits into its business processes. Misconceptions about how the research can actually apply to implementations and support can result in friction with other activities — and staff — that are entirely action-driven. To address this friction, we are involved in an ongoing effort to help our IT group understand our applied research and its practical outcomes. This is an ongoing effort, and we consistently look for new ways to demonstrate our research's practical applicability to the IT group.

Deliberation vs. Rapid Access

Another potential risk is in the contrast between deliberately planning for a technology service and the ability to offer teachers and learners quick access to technologies. Indeed, IT units founded on a deliberative process might view the research team as a disruptive force, and question both a new tool's reliability and the need for urgency. In the IT world, it is often easier to adopt a technology in the second or subsequent waves because many bugs are fixed after the initial test period.

To address this risk, we have argued that learning technologies evolve and are used on campus whether or not the central IT group reviews them. Because people bring their own devices and use free web services, it is not reasonable to expect or require all platforms and devices to be supported. Furthermore, IT units working with research teams can gather early warnings of technology disruptions and their implications. This collaboration positions IT units to be present during discussions of implementation and adoption and lets them respond in an agile way to campus needs.

Further, while initial findings seem disruptive, those findings could be used to guide a second round of more focused investigations that the IT group can help shape. For example, when we recommended that our campus adopt GAFE, the use of Google Plus Hangouts — though not a part of the formal Google Apps suite — became more feasible and widespread on campus. As a result, we will likely conduct a secondary study on using Google Hangouts for teaching and learning as compared to previously licensed tools. A second pass at our inquiry reinforces the iterative and developing nature of our research process, while also giving our IT group key information it needs to move a project forward.

If the central IT unit decides to implement a technology as a result of a pilot study, the research team will be challenged to integrate findings into the project development phase. In our early efforts, we wrote reports that explicated how a technology helps teaching and learning. We then delivered that report to the central IT development team, which acted upon our high-level recommendations (to adopt or not to adopt). However, the detailed recommendations and specific ideas for configuration and support were not adopted as effectively as they could have been in the project development stage. Following reflective conversations with senior IT management, we agreed that a better model was to engage an agent who could push the findings and represent user requirements on the project team. The agent could then actively explain the findings, translate them into technical requirements, and participate on project teams during service development. With this structure, the pilot's lessons learned and the researchers' intricate observations are preserved and supplied as needed to the IT department. We used this model recently, with a researchers participating on the project development team. Both IT staff and the research team agreed that it helped create a much better service for the campus.

Vendor vs. Researcher Goals

Another risk is related to the object of our inquiry, which is often sold by a vendor. Because of this, researchers might need to communicate with vendors both to access the technology and understand its features and functions. This can pose problems for researchers. Vendors are highly motivated to present their products in the best light, and they're highly unlikely to suggest other vendors' products — or no technology at all — as a better option. Vendors almost might seek to influence campus decisions, and — if the pilot results appear to endorse their technology — they may want to use the findings to market it to other universities.

Vendors can use findings to improve their products and articulate how their technology can be fruitfully used in teaching scenarios. However, research teams invest considerable time in pilot projects and do not view usability testing for vendors as a primary aim. To eliminate potential conflicts of interest, we recommend having a point person who is not on the RAIT team work with the vendor. That person can filter communications and deflect potential vendor influence.

Benefits

Engaging in this form of research has several benefits.

Speed

This method requires a relatively low investment on the part of the team members and the institution. In just three months, our team can run a pilot and produce a report describing the teaching and learning affordances a technology provides, as well as any support issues that might arise. Thus, a project can go from initial idea through pilot phase to adoption within an academic year.

Evidence-Based Adoption

The team's findings improve the IT unit's decision-making and planning processes and help the unit keep pace with emerging educational technologies. The central IT unit can envision early what support, security, and integration issues might arise if a specific technology is adopted. This makes the processes used to decide whether to support a technology on campus more rigorous. It also offers a way to synthesize the push from emerging technology adopters with the central IT unit's opposing force. The urgency of teachers and learners is balanced with central IT's need to consider important issues related to offering a technology at scale. The results of a RAIT team provide evidence-based recommendations for implementing technology in learning environments.

Community Building

RAIT teams encourage the organic growth of community and communication networks across organizational boundaries. Within our team, each researcher learned a great deal about initiatives and priorities both from others members' perspectives and from their own associated units. Beyond the team, study participants typically represented departments, schools, colleges, and programs across the campus. Inevitably, in focus groups and interviews, participants reveal new ideas, unrelated needs, and departmental initiatives, which inform both the researchers and other participants. These details and insights have directed the researchers' focus for future studies and informed planning for faculty–student support services. Finally, the study findings can also be shared with other institutions that can benefit from our local experiences, which serves to extend the community beyond the campus.

Faculty Support

One of the most significant outcomes and benefits of this process is that faculty members recognize the effort to help them manage the demands placed on their teaching practice. These efforts resonate with both early technology adopters and those who adopt at a slower pace. At our institution, the campus IT unit hears from early adopters who wish for responsiveness at the speed modeled by businesses such as Google. The IT unit must then explain the infrastructure, staffing, and funding issues that limit responsiveness. The RAIT team channels an early adopter's excitement, leveraging expert knowledge to explore best practices, sample scenarios, and future needs that can benefit the majority of campus users. Repeatedly, participants express gratitude both for the pilot opportunities as well as the potential for long-term solutions. The RAIT team demonstrates a campus commitment to improve teaching and learning with and through emerging educational technologies. Specifically, the team helps faculty decision making and reflective thought about how to choose, apply, and assess the numerous educational technology options that continually become available.

Considerations and Recommendations

Our experiences have yielded five guiding recommendations for those interested in adopting a similar model; each should be amended and revised to suit your individual institution's context. The recommendations refer to the five core considerations vital to successful implementation:

- Forming teams

- Identifying projects and needs

- Identifying participants

- Seeking institutional support

- Communicating impact

Forming Teams

Our team included a faculty member, IT manager, and librarian, but other just-in-time collaborations could engage a wide range of campus voices. Depending on the context, expertise, and established relationships, institutions adopting this model might choose to incorporate educational technologists, instructional designers, curriculum consultants, or interested administrators. The only essential criteria for screening membership are that all participants work collaboratively throughout the process.

Identifying Needs and Emergent Technologies

Inquiries and research projects that can generate the widest change and innovation will be specific to local needs and perspectives. The most direct method of identifying needs at your institution is to engage with learners and teachers in formal and informal settings. You might also explore less direct strategies, such as mining the feedback gathered by the central IT unit. Complaints or requests about educational technologies inevitably filter to IT; at our institution, for example, additional rapid assessments were conducted to evaluate the virtual private network, clicker support, iPad connectivity in teaching spaces, and Mendeley licensing. Each of these studies was a direct result of faculty and campus feedback delivered to the central Office of Information Technology. Other studies worth considering include hybrid class elements, assessment or student engagement in MOOCS, classroom response systems, and use of specific tools, such as Voicethread.

Local Applications

The structure and model described here suited our institution's specific climate, forces, and needs. Such a model can be adapted and revised in various ways to better meet local needs. For example, Pennsylvania State University has developed a model called hot teams. According to the Penn State Educational Technology Services (ETS) website [http://ets.tlt.psu.edu/ets-hot-teams/], a hot team is "a small group of instructional designers, technologists, faculty or other interested parties who are given a specific amount of time to quickly review a specific technology."13 Within a few weeks, hot teams produce and publish a white paper to the ETS website describing a tool's affordances for teaching and learning. Other models might include strategic monitoring of online communities and communications invested in educational technologies. Institutions might even choose to engage education or computer science students to participate in trend watching and assessment.

Identifying Pilot Participants

We recommend a few strategies for recruiting faculty participants who are innovative, risk-taking, and adopt emerging technologies based on our own (somewhat informal) method.

First, target local conferences that attract innovative teaching faculty. Our campus hosts an annual conference on teaching, learning, and technology, and we have made significant connections by presenting our results there and attending faculty presentations.

Second, establish a presence on Twitter or other social media and follow both institutional and national groups engaged in educational technologies. We also created a locally hosted blog in which we post our findings and related posts, publications, and examples.

Third, leverage personal networks on campus. Our relationships with colleagues, administrators, educational technologists, and faculty developers have been an ample source of recommendations. Connections with students have also helped us identify faculty members whose application of technology made significant impressions on students.

Finally, reach out to other campus units periodically and make every effort to extend networks and broaden the community. For example, you might consider hosting gatherings or events with groups such as graduate teaching programs, faculty development centers, and education-focused local or disciplinary research groups.

Seeking Institutional Support

We have conducted a few studies with this RAIT model, and the support of three separate university units — the central IT unit, the libraries, and disciplinary faculty — was absolutely crucial and valued. If the contributions from one of these field areas were missing, our inquiry would be less rich; therefore, it is especially important to give care and attention to each management chain.

We found it beneficial to explicitly articulate how the team's research reinforces each unit's values and mission. For example, a central IT unit would value knowing whether a specific technology has the potential for widespread adoption and could facilitate teaching and learning. Additionally, the unit could use the evidence-based information to shape a much more robust service for the campus.

From the University Libraries' perspective, the team's inquiries offer rich data about local users, specific needs, and future directions. All of these details inform the information and digital literacy education initiatives that the libraries spearhead. Furthermore, the chance to identify useful technologies, to integrate those with library services and resources, and to partner in campus support reinforces several components of the libraries' mission.

From the disciplinary faculty standpoint, the findings' discipline-based nature offers compelling evidence for new educational technologies' efficacy within specific disciplines. This allows faculty participants to reach a broad audience — such as professional societies — within their disciplines and achieve broader impact on their profession. Further, such discipline-based research is more likely to be viewed as rigorous scholarship by colleagues. Finally, faculty leaders and administrators can benefit from advanced information on how an educational technology might be used for the teaching within their academic units.

Communicating Impact

Our endeavor's intent has been to support teachers and learners confronting complex information and learning environments; in that spirit, we actively seek to widely distribute our findings, both negative and positive, to local and distant audiences. We do so through publications, presentations, discussions, and social media. RAIT's success relies on this final step of communication both for effecting change and demonstrating value to the institution and the scholarship of teaching and learning. We recommend developing your own communication strategy, which might include mile-post reports; culminating reports; informal and formal presentations; social media interactions; and local, national, and international presentations.

Conclusion

Our experiences with RAIT and the RAIT team have been fruitful and effective in our local context. Given the inefficiency of bottom-up and top-down models of technology adoption, RAITs can offer a compelling alternative for other institutions of higher education.

- Catherine McGloughlin and Mark J. W. Lee, "Mapping the Digital Terrain: New Media and Social Software as Catalysts for Pedagogical Change," Hello! Where Are You in the Landscape of Educational Technology? Proceedings Ascilite Melbourne, 2008, pp. 641–52.

- Evgeny Morozov, The Net Delusion the Dark Side of Internet Freedom, 1st ed., Public Affairs, 2011.

- Arne Duncan, "Letter from the Secretary," Transforming American Education: Learning Powered by Technology, National Education Technology Plan 2010, US Department of Education, 2010, p. V.

- Alison Head and Michael B. Eisenberg, "Truth Be Told: How College Students Evaluate and Use Information in the Digital Age," Project Information Literacy Progress Report, University of Washington Information School, 2010.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, New Millennium Learners. Initial Findings on the Effects of Digital Technologies on School-Age Learners, OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, Paris, 2008, p. 17.

- Grainne Conole and Panagiota Alevizou, A Literature Review of the Use of Web 2.0 Tools in Higher Education, Higher Education Academy, 2010.

- Catherine F Brooks, "Toward ‘Hybridised' Faculty Development for the Twenty-First Century: Blending Online Communities of Practice and Face-to-Face Meetings in Instructional and Professional Support Programmes," Innovations in Education and Teaching International, vol. 47, no. 3, 2010, p. 261.

- Rick Cummings, Rob Phillips, Rhondda Tilbrook, and Kate Lowe, "Middle-Out Approaches to Reform of University Teaching and Learning: Champions Striding between the Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches," The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning vol. 6, no. 1, 2005.

- Cummings et al., "Middle-Out Approaches," p. 10.

- Punya Mishra and Matthew J. Koehler, "Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge," The Teachers College Record, vol. 108, no. 6, 2006, p. 1029.

- Marie C. Hoepfl, "Choosing Qualitative Research: A Primer for Technology Education Researchers," Journal of Technology Education, vol. 9, no. 1, 1997.

- Mishra and Koehler, "Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge," p. 1018.

- Educational Technology Services, "Penn State Hot Teams" [http://ets.tlt.psu.edu/ets-hot-teams/], Pennsylvania State Education, Technology, Design, Innovation, Community; accessed 13 December 2013.

© 2014 Caroline Sinkinson, Mark Werner, and Diane Sieber. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 license.