Key Takeaways

- With one billion devices expected to have mobile broadband Internet connections, the impact of mobile communication cannot be underestimated.

- With this growth in mobile devices, it seems appropriate to ask what completely new things might be afforded by mobile media for learning.

- The discussion of learning environments and mobile media grants educators an opportunity to adopt methods of situated, contextual, just-in-time, participatory, and personalized learning.

- Theory aside, it seems common sense that instruction should be performed in the most authentic context possible to practice and demonstrate useful learning, which mobile learning environments can facilitate.

As I walk down State Street, a mile-long strip of eateries and shops near the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, I decide to try something new for lunch. In an instant, my cell phone is out and I touch a small black icon, launching Siri, a free app I downloaded while riding the bus the previous day. I press the record button and speak into my headset: "What's the best noodle restaurant nearby?" Three seconds later, a list of five restaurants appears onscreen, each with user reviews, online menus, phone numbers, reservation options, and business hours. A single touch yields a map with my current position and the best walking path to the restaurant I select.

While eating, I open the foursquare app with my free hand and touch the "Check in" button. This tells the service where I am and awards me a few points for doing so, continuing a silly competition with a few friends about who can earn the most points this week. Simultaneously, a tweet goes out from Twitter and my Facebook status is updated in case anyone I know wants to drop by for lunch. For five additional points I leave a tip for future patrons of the Vientiane Palace by typing, "The spring rolls are nice but a bit overpriced IMHO."

After dinner, the sun has set and I am in my backyard with my wife looking up at a particularly clear night. We see a very bright point in the north sky and notice that looks more orange than any of the other stars, which begins an ill-informed debate about whether or not it is a planet. A few seconds later, I launch the Star Chart app, and we hold the phone up above our heads between us and the sky so that the screen acts like a small window to the heavens. Full of stars, the screen tracks the sky as we move, turn, and point the device at different areas. In real time, the software connects the dots and superimposes the constellations on the points (see Figure 1). Another touch on the orange dot and we see a photo of Mars displayed as an overlay on the sky with information about its size and distance from Earth.

Figure 1. Using Star Chart on an iPhone

Mobile: A New Environment for Informal Learning

There are now more than 4.6 billion mobile phones in the world, according to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)'s February 2010 press release. This means that mobile has taken the place of FM radio as the most ubiquitous communications technology on the planet.1 To be fair, only one billion devices are expected to have mobile broadband Internet connections, but even with that clarification, the impact of mobile communication cannot be underestimated. When compared to FM, the current shifts in communication, knowledge, and collaboration become clear (see Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Communication over FM Radio vs. Mobile Phones

| Characteristics | FM Radio | Mobile Phone |

| Network model | Centralized | Peer-to-peer |

| Content customization | Uniform | Personalized to context |

| Information distribution | Just-in-case | Just-in-time |

| Role of audience | Consumer | Equal participant |

| Reliability qualifier | Authority | Social capital |

| Governance | Institutional | Relational |

It might be safe to say that each time a new medium appears, no matter how different it is from the last, the normal reaction of first adopters is to use it as a new package for existing content. In the case of mobile education, some leaders of this effort are Apple's iTunesU, BlackBoard Mobile, and the Amazon Kindle. Let me suggest that these efforts represent the least creative uses of mobile media. They simply repackage, with minor advances, what is already available through other forms. Lectures are still lectures, and course management is still course management. Even so, the first time I watched a computer science lecture from Stanford University (while exercising), I knew something fantastic was taking place. In the same vein, accessing course calendars and readers while riding a bus is quite convenient and will surely become a common activity. Giving respect where it is due, it seems appropriate to ask what completely new things might be afforded by mobile media for learning.

After nearly four years of studying and designing video games in higher educational settings, I've seen that the introduction of new technology can provide a reason to rethink a course from the ground up and reassess its core educational goals. Often the greatest educational benefits seem to come from this process, not just the technology that encouraged it. In the case of mobile learning environments, I have taken notice and facilitated a few designs that leverage the unique strengths of the medium in concert with previously theorized educational approaches.

Inspiring Educational Designs

A few examples of mobile technology used for learning and research demonstrate innovative applications:

- Dow Day

- Mentira

- WeBIRD

Dow Day: Place-Based Learning

It can be easy to forget that we human beings are more than brains connected to an apparatus that moves us around in space. Instead, we belong to communities, we live in neighborhoods, we have local culture and events. Inquiry into these real things led to many of the fields we now call science, literature, mathematics, and history. Why then do we isolate instruction in those fields to a classroom, instead of deriving instruction from the environment from which these subjects originated?

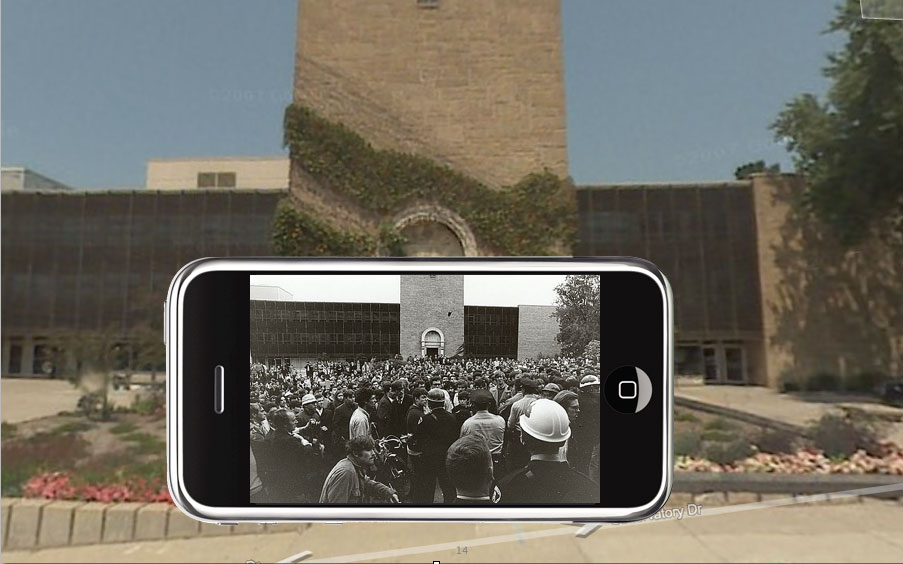

The Local Games Lab, a research team out of the Games, Learning, and Society group at UW–Madison, has produced a number of mobile curriculum designs that demonstrate place-based learning.2 One such example, Dow Day, is a mobile documentary that relives the student protests of 1967 in Madison, Wisconsin, against the Dow Chemical Company. In this activity, location-aware handheld devices add an augmented layer of history to a walk through the campus, placing the student in the role of a news reporter. By monitoring the device's GPS, Dow Day creates the illusion of additional characters standing in physical space and facilitates simulated conversations with these historical entities. In addition, when players walk to predefined media locations, they trigger video footage showing the physical scene from 40 years ago, effectively superimposing the marchers and police onto the current landscape (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dow Day Experienced on an iPhone

The goal of this design was to give students an active, experiential, embodied role in the events of history instead of just hearing about them. The stories that contribute to the heritage of UW's campus are brought to life and relived by students today through a designed experience.3

Mentira: Situated Learning

Situated theories of cognition claim that knowing and doing are inherently linked.4 Theory aside, it seems common sense that instruction should be performed in the most authentic context possible to demonstrate useful learning. Unfortunately, due to numerous logistical and epistemic barriers, formal education is often forced to disregard this advice, conducting learning in decontextualized environments. There are exceptions.

One such example is a mobile game called Mentira, produced at the University of New Mexico. The game is designed to teach an introductory college Spanish course in ways that are contextually sound for language learning. In the first unit, students play a mystery game on handheld devices in class, taking on a role and a goal within a story told completely in Spanish. In the second part, the class moves outside to a local Spanish-speaking neighborhood where they continue the story while interacting with physical and virtual Spanish speakers in real places (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Situated Learning with Mentira

With Mentira, students learn Spanish outside the classroom through narrative and interaction with members of a Spanish-speaking neighborhood, re-situating language in practice.

WeBIRD: Citizen Science

For many disciplines, scientific observations are laborious but do not require extensive training to perform. Even more interesting, some of these areas already have hobbyist communities that engage in similar work for entertainment or out of simple curiosity. For example, professional horticulturists working for a research institution might investigate optimal pH levels for growing a particular species of blueberries, while hobbyist gardeners have kept a paper log of the same data over the previous few seasons.

Identifying the disconnect, a small team from the Animal Science and the Academic Technology departments at UW–Madison are working on a prototype for hobbyist birdwatchers. WeBIRD aims to crowdsource ornithology research by providing a tool for hobbyist practitioners. A birder will record the audio of a bird heard out in the field and have the system identify the species while logging the sighting's location, current weather, time of day, and date to a central database. This data can then be used for anything from formal research of migration patterns over time to individual questions such as, "Where am I most likely to see a cardinal this time of year?" The potential for location-aware, casual gaming structures such as birder achievement badges and leader boards are also being investigated in order to provide additional social play motives for participation.

Get Involved

Stay Connected: If you have mobile learning designs, tools, or tales to share, join the Games, Learning, and Society Mobile Learning Facebook group at http://bit.ly/bHpure to stay in touch with our group of researchers, designers, and events we host.

Make Mobile Learning Experiences: If you would like to use our open-source tool to begin designing locative tours, stories, or games right now, request to join the ARIS Games Alpha Editing program at http://arisgames.org.

Conclusion

Learning happens anywhere someone has questions and the means to explore answers. As ubiquitous access to information continues to shift toward personal mobile devices, more and more of the learning that takes place may be happening outside of the classroom and in the context of a backyard conversation, a walk through campus, or a Taquería in New Mexico.

It may just be that the discussion of learning environments and mobile media grants educators an opportunity to learn from the situated, contextual, just-in-time, participatory, and personalized learning that takes place as soon as class ends. Creativity in curricular design might minimize the gap between mobile media and FM radio communication characteristics so that educational environments blend into the rest of a student's life and vice-versa.

- Tomi Ahonen, Mobile as 7th of the Mass Media: Cellphone, Cameraphone, iPhone, Smartphone (London: futuretext, 2008).

- Kurt D. Squire, Mingfong Jan, James Matthews, Mark Wagler, John Martin, Ben Devane, and Chris Holden, "Wherever You Go, There You Are: The Design of Local Games for Learning," in The Design and Use of Simulation Computer Games in Education, B. Sheldon and D. Wiley, eds. (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishing, 2007), pp. 265–296.

- Kurt D. Squire, "From Content to Context: Videogames as Designed Experience," Educational Researcher, vol. 35, no. 8 (2006). pp. 19–29.

- John Seely Brown, Allen Collins, and Paul Duguid, "Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning," Educational Researcher, vol. 18, no. 1 (January/February 1989), pp. 32–42.

© 2010 David Gagnon. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Unported 3.0 license.