Key Takeaways

- Peer review of online courses can be done at a distance using a combination of asynchronous course visits and synchronous discussion with online meeting tools.

- This technology-mediated approach gives online faculty the opportunity to experience an unfamiliar course interface from a student's perspective, encourages a focus on design elements distinct from course content, and promotes a feeling of community.

- IT personnel can enhance this process by providing faculty with archived peer-review sessions and detailed "how to" instructions, while also facilitating their hands-on experience with new technologies.

In the summer of 2009 we participated in the inaugural Quality Matters Faculty Development Workshop at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC). Quality Matters (QM), according to its website, is a "nationally recognized, faculty centered, peer review process designed to certify the quality of online courses and online components," and the QM workshop was part of a wider UNC initiative to expand and improve online offerings. Although originally conceived as a face-to-face meeting, the workshop was conducted online because of scheduling issues. As a result of our workshop experiences, we believe that a purely online, technologically mediated peer-review process has many benefits, including:

- A sharpened focus on best practices in course design

- Faculty training on the use of online collaboration tools

- Development of community among interdisciplinary faculty teaching at a distance who might never meet face-to-face

Synchronous and Asynchronous Review

Formal QM course reviews are conducted asynchronously using a 40-element rubric that emphasizes alignment across critical course components. A course review usually involves three peer reviewers, including one subject matter expert who can make determinations about elements that might be affected by specific course content. Participants in the UNC workshop separated into teams of two faculty members and focused almost exclusively on course design because no subject matter expert attended. Given our ongoing collegial relationship, we decided to pair up even though Carrie, a Spanish language instructor, was in Argentina at the time, while Nancy, a philosopher, was in Colorado. We each chose an introductory course to review: Spanish 101 and Philosophy 100. Throughout the workshop and the peer-review process, we used the Blackboard E-Learning Course Management System (version 7.3) augmented by the Wimba Collaboration Suite for Higher Education, taking full advantage of both synchronous and asynchronous tools.

Asynchronous Collaboration

To facilitate the peer-review process, our Blackboard administrator gave us "teaching assistant" privileges so that we could each take an independent look at the other's course. In addition to the flexibility of place and time, we had the opportunity to reflect individually on the significance of the course design elements emphasized by the QM rubric.

Asynchronous collaboration called our attention to the importance of course design. Specifically, asynchronous review gave us a true "student" view of the other's course. Precisely because the instructor was not present to indicate where to find information and how to proceed through the course materials, we experienced what it was like to navigate an unfamiliar content environment for the first time. This gave us insights into our own course design, in addition to helping us formulate recommendations about how to improve the other's course. More generally, it gave us a new appreciation for how important it is to organize content in a way that novice learners in any discipline will find intuitive to navigate.

The QM rubric also guided our thinking about design elements, but we believe the experience of navigating an unfamiliar environment was the most important factor in our appreciation for course design. This learning would not have been as significant in a synchronous environment and probably was enhanced by the fact that neither of us had any expertise in the other's discipline.

Synchronous Collaboration

Synchronous collaboration enabled us to identify common struggles even though we teach very different kinds of content. We used Wimba Pronto and Wimba Classroom to collaborate and connect as two faculty members with common goals, but any tool that allows for real-time audio and visual connection would serve this purpose. We relied on the Pronto chat tool (both voice and text) to have short conversations regarding the logistics of the peer-review process. Although we could have done this via e-mail, Pronto enabled us to establish a social presence because we often began with a few minutes of informal conversation, and we both uploaded profile photos. Carrie was already using Pronto in her courses, but as a result of this experience, Nancy began encouraging her students to use Pronto rather than e-mail. In her case, direct exposure to the technology taught important lessons about course design and delivery. It is easy to assume that voice tools don't really matter unless the course content includes an emphasis on public speaking, but Nancy's experience convinced her of the benefits of incorporating alternative modes of communication.

The multimedia environment provided by the Wimba online classroom enabled us to share desktops while discussing parts of a course we were viewing at any given time. In this part of the peer review, we each guided the other through our own course in order to focus on areas where we especially wanted feedback. Our conversations moved freely between discussions of what it was like to experience each course as a student, the challenges we each faced with respect to organizing our course content, and the reasoning behind our initial decisions of which tools to incorporate into our course design. The visual interface enabled us to literally "see" the other's reasoning in action as we were talking.

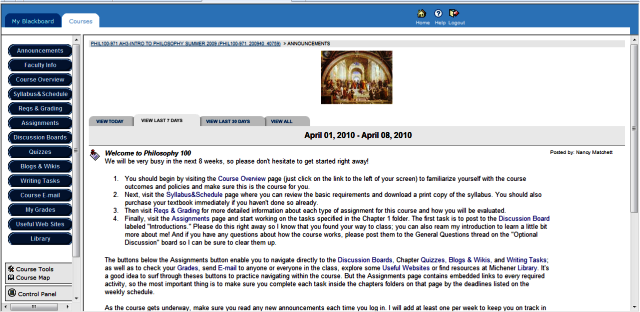

In one session, Nancy navigated through her Philosophy 100 course while Carrie provided feedback. We began on the home page and then discussed each main element of the course (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Home Page for Philosophy 100

Although Carrie had no background in philosophy, we quickly recognized that we face similar challenges when setting up our courses, even though we made different decisions about how to deal with them. For example, Nancy posts a detailed welcome message in the home page of her course, which disappears later in the term. Her reasoning is that this information becomes superfluous after the first few weeks, and she deliberately uses her message to engage students in the process of navigating to all the key areas they will need to access throughout the course. She chose to provide sidebar buttons for every tool used in the course while also linking to those tools within specific learning units. Her reasoning here is that while some students prefer to navigate through the learning units step by step, others prefer to print and follow her detailed syllabus, completing as much work as possible offline and logging in just to submit discussion posts and other assignments.

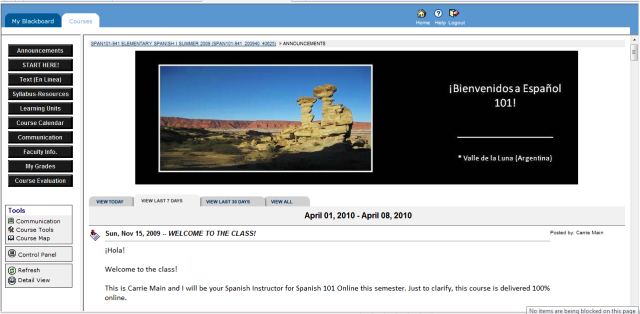

By contrast, Carrie's Spanish 101 course takes a more streamlined approach, posting links to tools only within specific learning units where students would use them. Carrie also provides a fixed "Start Here" button available throughout the course (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Home Page of Spanish 101

Carrie's reasoning is that because students must complete nearly all of their learning online, they get in the habit of navigating immediately to the Learning Units page and quickly learn to treat all the other buttons in the sidebar as places to go only in specific circumstances. Hence the Start Here button does not stand out as superfluous. Because Carrie uses a textbook with a companion website containing quizzes and other learning activities, students in her course are essentially working with two sites, making clear navigation instructions essential. She uses her Blackboard learning units to link students to specific areas of the companion site so that they don't have to learn two interfaces at once. Nancy didn't need any familiarity with foreign language-teaching to understand why this was important.

Three recurring themes appeared throughout both sessions:

- One concerned how to "nest" various types of content. We frequently shared ideas about how to make sure students could easily find information they needed without the site becoming cluttered with redundant information.

- A second was how to establish a social presence for the instructor. Carrie's goal of increasing spoken language competence leads her to use voice conferences with students for this purpose, while Nancy's goal of enhancing skill in written argumentation leads her to use daily discussion board interactions.

- A third was how to harness new technologies wisely. We agreed on the need to make sure we were using new tools in order to meet course objectives, rather than simply incorporating them because they were new. The fact that we were using different browsers and operating systems also called our attention to formatting issues of which we had been unaware.

Again, it was the ability to literally see each other's reasoning that led to the deepest insights. Much of this learning would not have been possible face-to-face.

Sample Peer Review Archives

Spanish 101

This audio archive covers:

- The use of both graded and ungraded assignments

- Deciding which tools and how many tools to incorporate

Philosophy 100

This audio archive covers:

- Advantages of using audio

- Different technologies for incorporating voice into a course management system

Integrating with Information Technology

Participating in a technology-mediated peer review also provided an opportunity to practice with Wimba tools that were fairly new to us. Although we both tend to be early adopters, more likely to be intrigued than threatened by new technologies, we still experienced some glitches. Since technology problems might lead faculty who are less comfortable with technology to simply give up on the process, we believe easy-to-access tech support is essential to the success of online faculty development workshops. We did a lot of troubleshooting during our course review sessions, which were recorded. Because these conversations were archived, the technical support team at our institution can use them to hear how faculty struggle with new technologies and to find gaps or errors in their currently published support materials.

Though not solely an outgrowth of the online peer review workshop, UNC's Blackboard support page now routinely includes both an "Instructional Use" guide explaining why a faculty member might incorporate a particular tool and a "Quick Reference" guide detailing steps for using the tool. Hence, an additional benefit of the purely online faculty development workshop is that it helps both instructional technologists and online faculty understand each other's environment.

More generally, the purely online workshop also helped us learn about the variety of technological solutions that can be used to solve common faculty problems. The specifics of our own case led us to consider the relative merits of a printable course schedule versus an online calendar and task list, compare strategies for archiving and reusing course elements, and find ways to integrate publisher-provided content and external links into our course design. Other faculty pairings would no doubt yield different lessons. Since archives of both asynchronous and synchronous discussions can be shared, faculty who participate in such workshops can help IT professionals understand what sorts of new tools will probably be most useful to faculty and students and how best to support their institution's use of those tools. We recommend that IT professionals be fully integrated into the workshop process itself, to make sure faculty can take full advantage of live classroom technologies that often intimidate newcomers.

Building Community at a Distance

Although we learned a lot about course design and the use of new technologies, we believe the most valuable aspect of the online peer-review workshop is the way it constructs a community among faculty from very different academic disciplines who might never meet face-to-face. Nancy's primary motive for participating in the workshop was to gain professional credentials (both of our courses are now certified by our institution as meeting QM standards, and both of us have been certified as course reviewers by the QM organization), while Carrie was eager to maintain some connection to other UNC faculty because she had just moved to Argentina. Our disciplines have little in common, yet participation in this process deepened our appreciation for each other's teaching skills and cultivated the sense that we are involved in a shared enterprise. This feeling extends to the other members of our 2009 faculty cohort, with whom we discussed the QM rubric and more general issues of course design. To a lesser degree, it also extends to members of this year's workshop cohort to whom we have granted access to our archived courses, giving them the opportunity to listen to our peer-review session archives, and to members of the Instructional Technology/Instructional Design team with whom we have communicated at various points both during the workshop and since. Here again, the fact that the workshop was conducted purely online made these connections possible: in March, Carrie used the Wimba Live Classroom tool to showcase both Philosophy 100 and Spanish 101 to faculty members participating in the 2010 QM training.

Online peer reviews are not the same as face-to-face discussions. There is a slight time delay when using any chat tool, and the lack of visual cues can occasionally make it difficult to know just how your comments are being received or whether your message is getting through. Still, experiencing these effects of technology-mediated communication is itself an important lesson for anyone who teaches online. And as we have emphasized, technology-mediated collaboration also has advantages over face-to-face discussion. Online peer review benefits distance education course design quality by enabling faculty to literally see the results of design choices made by their colleagues, providing opportunities to navigate unfamiliar course environments, encouraging extensive use of collaboration tools, and connecting faculty to each other as well as to IT professionals. For these reasons, a course design workshop that incorporates online peer review can be a valuable professional development tool for any campus.

© 2010 Nancy J. Matchett and Carrie Main. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.