Key Takeaways

- To address exponential growth in online learning, the University of Central Florida expanded its faculty development program, focusing on offering more effective and efficient training in online instruction.

- This case study evaluates the results: a redesigned course that focuses on increasing use of communication tools, collaboration, and efficiency.

- In addition to meeting practical goals, the formative and summative evaluation results during the summer and fall pilots indicated a high level of satisfaction among faculty participants with the interaction/collaboration opportunities, concept application, and hands-on activities.

Over the past five years, the online learning initiative at the University of Central Florida (UCF) has grown exponentially. Compared with the previous academic year, for example, the increase of online learning in 2011–2012 accounted for 94.15 percent of the growth in UCF's student credit hours, including 32.27 percent of the overall hours, 43.03 percent of the graduate hours, and 73.62 percent of the regional student hours.1 This growth trend created a need for an expanded faculty development program to prepare UCF faculty to teach online. Thus, in 2010 the university's Center for Distributed Learning (CDL) redesigned our flagship faculty development course in interactive distributed learning (IDL6543) to provide more effective and efficient training to accommodate the increasing demands for online learning.

In this case study, we evaluate the redesigned course IDL6543. Following a brief review of the literature on measures of effectiveness in faculty development, we discuss the history of IDL6543 and the context for redesigning the course. We then describe the redesign process and new course design, as well as our evaluation and lessons learned.

Literature Review

Researchers have conducted a series of reviews on faculty development over the past three decades.2 The reviews show that distance education faculty development has evolved in terms of format, design, and effectiveness. In particular, research shows that effective faculty development maintains a balanced focus on content, pedagogy, and technology.3 Successful programs engage faculty with real-world course development experiences, offer all participants flexibility as adult learners with busy work schedules, and nurture a sense of connectedness and collegiality among faculty participants.4 We therefore focused our study on evaluating whether these evidence-based strategies had been successfully integrated in the IDL6543 redesign.

Research measuring the effectiveness of faculty development has always been very limited.5 The traditional satisfaction-rating method could not accurately evaluate faculty performance and engagement. Other measures have also been used to track changes in instructional practice, including pre/post questionnaires, interviews, teaching projects, portfolios, and student feedback.6 Researchers have been searching for assessment methods to evaluate faculty development in a more meaningful and systematic way.

In recent years, learning analytics has emerged as a new assessment method for measuring learning performance and effectiveness.7 Compared with traditional methods, analytics offers just-in-time and objective insight into individual learning practices, the learner's degree of engagement with peers and course materials, and the development of effective learning communities.8 Therefore, to evaluate the effectiveness of the faculty development program in our study, the data we used included different aspects of course analytics — such as usage analytics and online social interaction visualization — in combination with formative and summative evaluation results from faculty participants.

Redesign History and Context

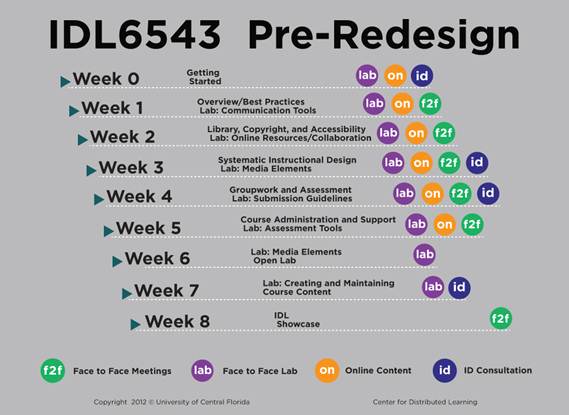

The IDL6543 course gives faculty members the technical and pedagogical foundation needed to design and develop effective online courses. The original course content was designed and delivered in 1998. Faculty participants were required to attend eight weekly face-to-face lecture-based workshops. They also attended technical labs and instructional design consultations, and completed weekly online modules (see figure 1).

Figure 1. IDL6543 pre-redesign overview

Although mandatory course updates and maintenance were conducted yearly, major curriculum reviews and course revisions were conducted approximately every five years. Following a Developing a Curriculum (DACUM) process, the first course revision was conducted in December 2004, led by Steve Sorg, the assistant vice president and director of CDL.

IDL6543 Redesign Context

In spring 2010, Tom Cavanagh, CDL's new assistant vice president, formed an IDL6543 review committee to assess the current satisfaction level with IDL6543, review other institutions' professional development initiatives, and decide if another substantial redesign was necessary.

The review committee, consisting of online faculty from different disciplines, UCF college administrators, and CDL instructional designers and executives, began with an informal survey of faculty members who had completed IDL6543. The committee also organized site visits with local institutions to review their faculty development programs. At the conclusion of the committee's examination, the review committee identified sufficient issues to warrant another major redesign of IDL6543.

In addition to the review committee's feedback, our redesign team compiled past course evaluations by IDL6543 participants. The CDL executive team also identified and added to the redesign's desired outcomes. These outcomes fell into two basic categories: faculty needs and institutional needs.

To meet faculty needs, IDL6543 graduates requested the following changes:

- Provide faculty with hands-on activities to build their online course earlier in the process.

- Deliver the course with more online components and fewer face-to-face requirements.

- Reduce the lengthy materials on theory and provide best practices examples and an application of concepts through scenario-based learning.

- Provide more interaction and feedback from other faculty participants in the course.

- Streamline the course delivery and content, and consider the faculty member's various commitments on campus (such as course loads, research assignments, and departmental responsibilities).

- Recognize prior online teaching experience.

To meet institutional needs, administration requested the following changes:

- Increase the number of faculty participants from 30 to 40 each semester.

- Deliver IDL6543 three times a year instead of twice, increasing the number of credentialed yearly graduates from 60 to 120.

- Streamline the course delivery process to reduce the required resources (including instructional designer hours and classroom space).

In summary, given the rapid changes in technology, the varied teaching and technical backgrounds of our faculty participants, the increase in learning management system (LMS) features, and the rapidly growing demands for online learning, we needed to redesign IDL6543 to be a leaner, more practical, and more scalable program.

IDL6543 Redesign Process

In August 2010, we formed a redesign team consisting of five instructional designers; our task was to design and develop the new faculty development program, with a summer 2011 delivery date. We also identified the stakeholders — including CDL executive team members and IDL6543 graduate faculty members — who would provide feedback throughout the redesign process.

The accompanying video (4:53 minutes) considers the IDL6543 redesign process from the perspectives of faculty members, CDL executives, and the instructional designers.

The redesign team compiled research outcomes and feedback from IDL6543 graduates, CDL executives, instructional designers, and other stakeholders and identified the following redesign goals:

- Create a more scalable and sustainable faculty development program.

- Provide project-based learning throughout the faculty development program.

- Provide opportunities for collaboration and community building throughout the faculty development program.

After identifying the goals, the team began the design and development process by creating a course blueprint and a T-slice to represent one unit of instruction. After several iterations, we finalized the course outline and began development. Throughout the design and development process, the instructional designers received continuous feedback during monthly meetings with the stakeholders.

Outcome of the Redesign

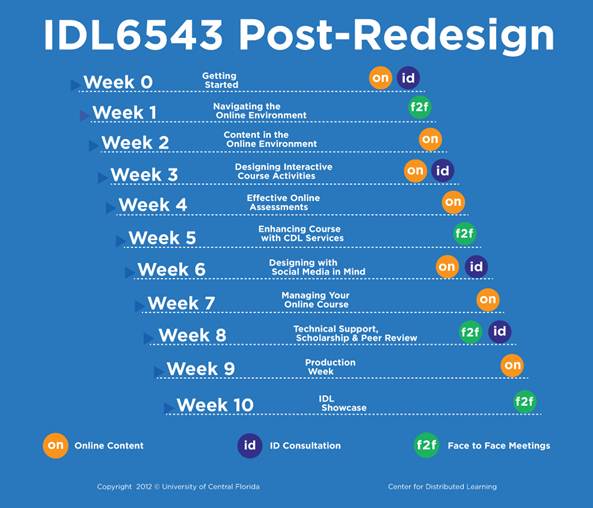

The redesign's outcome was a more blended 10-week course consisting of three face-to-face workshops, seven weeks of online content, a self-paced "Build Your Course" project, four one-on-one instructional designer consultations, and a faculty showcase (see figure 2; a more detailed outline of the redesigned course is also available for download).

Figure 2. IDL6543 post-redesign overview

Our redesign team drastically reduced the face-to-face requirements from nine required full-day sessions to three sessions (one full day and two half days) to provide more flexibility for the faculty. We designed the face-to-face workshops to be less lecture-based and more interactive with small and large group discussions and presentations by faculty web veterans.

Anonymous course evaluation feedback from fall 2011 was positive:

"The structure and organization of the readings was great and the content was presented in a way that was easy to understand. I liked being guided through activities…"

"I like that it wasn't purely theoretical, and that we started building 'our' own course from the beginning. That hands-on aspect was so helpful in encouraging me to prioritize assignments and in helping me to implement some of the more abstract ideas we discussed."

"I enjoyed the mixed-mode method. It provided both structure and flexibility, given the busy nature of most faculty members."

For the online content, we reduced the lengthy material on theory and provided focused applications of concepts through best practices examples and scenario-based learning. To streamline the online content, we briefly introduced concepts, provided instructional strategies on how to apply these concepts to online courses, and offered optional readings and resources for faculty members who wanted to learn more about a specific topic.

Additionally, we linked to authoritative sources in the online content rather than place all of the content in the course to reduce the need for content updates.

We also designed online content and activities to directly align with the Build Your Course project activities. Faculty members can thus read about a topic and then apply the information to building a course component. The Build Your Course project activities include choose-your-own-path options, which give learners choices and thereby recognize their prior technical experience; they also offer faculty members the flexibility to focus on skills and media that are relevant to their pedagogical and course design needs. The Build Your Course project begins early in the course to provide hands-on and project-based learning from the start.

We included additional opportunities for interaction and feedback throughout the course. The one-on-one instructional design consultations were strategically placed to provide interaction during the online weeks and an opportunity for faculty members to receive feedback on their Build Your Course efforts. We also incorporated online and face-to-face small-group discussions, web-veteran presentations, and a peer-review session to provide more peer interaction and feedback throughout the course.

The redesign streamlined the course administration. We clearly identified the roles of everyone supporting IDL6543 (including the team lead, instructional designers, course facilitators, and a task master) and created detailed checklists for each role to ensure consistency and efficiency.

We reduced the instructor role for the course's face-to-face and online portions from a team of 10 instructional designers to one, along with one UCF IDL6543 graduate faculty fellow. We chose to leave the instructional design instructor free from assigned one-on-one faculty consultations during the semester they taught the course because of the increased workload from facilitating the course's online and face-to-face portions. The other instructional designers shifted their focus to one-on-one consultations with their assigned faculty members each semester.

Instructional Design Team Lead Denise Lowe explains the changes in the instructional designers' role as follows:

"The revisions to the IDL6543 program have resulted in several changes for the instructional designers. The decrease in the weekly face-to-face delivery commitments allows more time for in-depth course design, and changes the instructional role to facilitation. The consultations are now the primary contact venue in which more analysis and creativity in course design can be explored with the faculty. Although change can require a paradigm shift in thinking, the redesigned IDL6543 provides a more focused, targeted approach to course design in which faculty and instructional designers work together to improve the quality of online instruction."

Redesign Evaluation

To evaluate the course redesign's effectiveness, we compared the course learning analytics and course surveys two semesters prior to the redesigned course's delivery and two semesters after the delivery. Specifically, we wanted to determine whether we achieved the redesign goals in terms of course design and faculty engagement. The course analytics consisted of the tracking data collected from the LMS, such as use of communication tools and average user login session lengths and frequencies. We used Excel to generate data visualizations and the Social Networks Adapting Pedagogical Practice (SNAPP) tool to map out the learner interactions in the online course discussions. The course evaluation data were compiled from the weekly and final faculty evaluation survey responses.

The data was generated from four cohorts totaling 129 faculty participants in the old IDL6543 in the summer (N = 24) and fall (N = 39) semesters of 2010 and the redesigned IDL6543 in the summer (N = 23) and fall (N = 43) semesters of 2011.

Increase in Use of Communication Tools

As figure 3 shows, a review of the redesign course's LMS tool usage analytics showed an increase in the use of communication tools — such as announcements, assignments, discussions, mail, and my grades — in the course's online portion. The most significant increase was in the number of times the announcements tool was accessed each semester. Use of the discussions tool nearly doubled in the redesigned course, while use of the assignments, mail, and my grades tools also increased following the redesign.

Figure 3. Use of online communication tools

The increase in the use of the announcements and mail tools can be attributed to the redesign effort to streamline the communication process by keeping the majority of all course-related communications within the LMS and reducing the instructor role from 10 instructors to two. The increase in the use of the discussions and assignments tools is a result of creating activities based on course design concepts, scenarios, and project-based learning throughout the course.

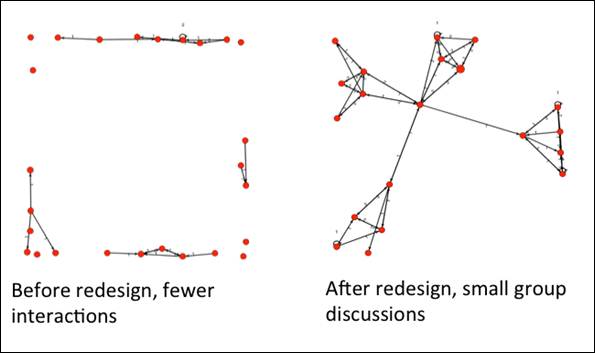

Increase in Interaction

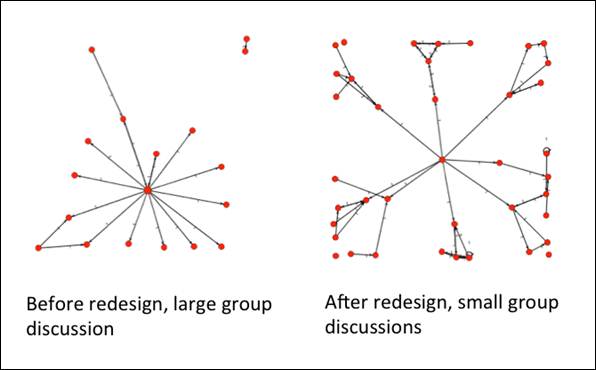

An analysis of the online discussion boards showed an increase in online social interaction patterns, specifically student-to-instructor and student-to-student interaction. As figures 4 and 5 show, before the IDL6543 redesign, the SNAPP screenshots indicated a linear discussion pattern. At that time, most faculty participants — indicated by individual red dots in the SNAPP screenshot — interacted only with the facilitator (indicated by the center red dot in figure 4). Few peer interactions were observed. After the IDL6543 redesign, we facilitated small-group discussions based on scenarios throughout the course to promote community building. We also facilitated a small-group discussion in the first face-to-face meeting so participants could meet their small groups before the first online discussion. The SNAPP screenshots of the revised IDL6543 discussions show a spider-shape interactive communication pattern, indicating an increase in interaction among peers (figures 4 and 5). The increased interaction in online discussions is likely a result of the redesigned activities, which reduced redundancy between online and face-to-face activities, provided more structure with specified deadlines, and engaged learners with scenario- and project-based learning.

Figure 4. SNAPP analysis 1: Interaction visualization of copyright discussion

Figure 5. SNAPP analysis 2: Interaction visualization of objective and interaction discussion

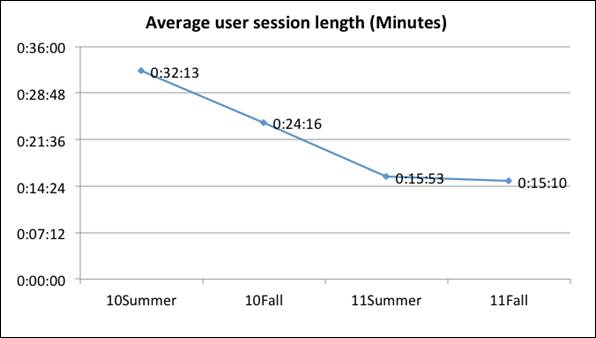

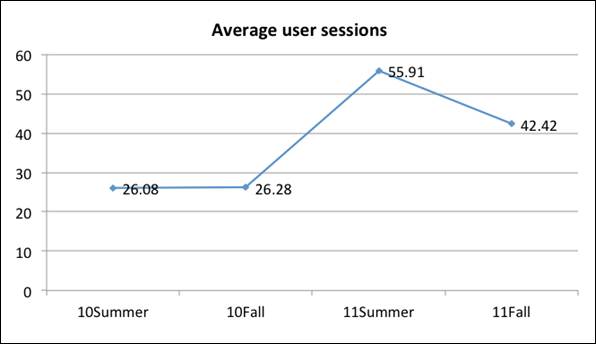

Increase in Efficiency

As figure 6 shows, we compared the average user login session length and frequency across the four semesters to represent another aspect of change in course engagement. Before the redesign, faculty participants spent an average of 32 minutes per session in summer 2010 and 24 minutes in fall 2010. After the IDL6543 redesign, participants' average session length decreased significantly to approximately 15 minutes for both summer and fall 2011.

Figure 6. Average user session length

On the other hand, faculty logged in far more frequently after the redesign (figure 7). In 2010, each participant, on average, logged in 26 times per semester. After the redesign, the login frequency per semester doubled to 56 for summer 2011 and 42 times for fall 2011. This data shows that our faculty participants logged in to IDL6543 more frequently for smaller chunks of time, which indicates an increase of efficiency in the redesigned course.

Figure 7. Average frequency of user sessions

The improved efficiency is likely a result of various new course features, including reducing lengthy theory elements, carefully chunking content into appropriate lengths, providing optional readings for participants, and linking to more practical examples from other online faculty members and relevant resources. We also attribute the increase in efficiency to the choose-your-own-path options provided in the Build Your Course project throughout the course.

Increase in Overall Satisfaction Levels

We used faculty surveys for formative and summative evaluation. Formative evaluation results during the summer pilot indicated a high level of satisfaction with the course's interaction/collaboration opportunities as well as the application of concepts and hands-on activities. As figure 8 illustrates, summative evaluation results showed an increase in participants' course satisfaction ratings compared to the previous IDL6543 version. Prior to the redesign, 83 percent of participants in summer 2010 and 75 percent in fall 2010 were either very satisfied or satisfied with the course. Following the redesign, 100 percent of participants in summer 2011 and 93.5 percent in fall 2011indicated they were either very satisfied or satisfied with the course.

Figure 8. Faculty satisfaction ratings before and after redesign

The faculty survey response rate before the IDL6543 redesign (30 percent) was far lower than after the redesign (82 percent). To validate the quantitative data, we also reviewed the qualitative comments in the surveys. Participant comments in the formative and summative evaluations of the redesigned course (summer and fall 2011) show a significant increase in the overall satisfaction level with the redesigned course. Faculty members stated that they:

- Enjoyed the small-group interaction both face-to-face and online

- Found that feedback from the instructors, instructional designers, and fellow IDL6543 participants was very useful in developing their courses

- Felt that not all readings applied to them and appreciated having access to optional readings and relevant resources throughout the course

- Found face-to-face class time to be wisely used and that meeting classmates again after weeks of online activity was helpful

- Felt that their experiences as students in mixed-mode courses was useful when developing their online courses

- Liked the hands-on activities each week to build course components

- Found the peer review session during week 8 beneficial because it let them get feedback from peers and a fresh perspective on their course elements, as well as letting them see what other faculty participants had developed

Lessons Learned

The evaluation results suggest the effectiveness of our newly redesigned IDL6543, which resulted in an increase in efficiency, interaction, and level of faculty satisfaction. As we now describe and our evaluation results show, our project achieved all three IDL redesign goals.

Goal 1: A scalable, sustainable faculty development program

Streamlining the course content and delivery and clearly defining the roles of all staff involved made course administration more scalable and sustainable; we were also able to increase the faculty enrollment each semester without increasing staff. Reducing the instructor role from 10 to two instructors resulted in more interaction and consistency in the online and face-to-face portions of the course. To prevent the curriculum from becoming inflated again, we decided to conduct an annual review of content rather than updating content each term. All of these changes let our faculty development initiative better meet the demands of technology changes, department needs, and UCF growth — and resulted in a more efficiently run course.

When designing a faculty development program, it is important to consider how many people you have to support it and clearly define roles to effectively and efficiently manage the course. Our lesson here was that communication among all staff involved is key to effective and efficient faculty development program management. Throughout the design and development process, frequent status meetings and detailed checklists improved communication and helped avoid duplication of efforts by those managing the course.

Goal 2: Pervasive project-based learning

By providing more practical application of concepts and project-based learning from the start of the faculty development program, there was an increase in efficiency and faculty satisfaction. The redesign included opportunities for learner choice, which recognized prior technical experience, addressed varying technical skill levels, and allowed faculty to meet their pedagogical needs. Such an adaptable design provides faculty with real-world course development experiences and provides flexibility for adult learners.

Here, we learned that by placing the majority of the course online, we needed to accommodate and support faculty participants with a lower technical skill level. We addressed this issue by strategically placing consultations with instructional designers throughout the course and providing optional open labs.

Goal 3: Collaboration and community building

The increase in course interaction and level of satisfaction is largely due to the redesigned community-building activities, including small-group discussions, peer review, instructional designer consultations, faculty mentorship, and web-veteran presentations. These collaboration activities integrated throughout the redesigned course provide opportunities for interaction and peer feedback among faculty participants and build professional collegial relationships between faculty participants and their colleagues, facilitators, and instructional designers both during and beyond the professional development program. Here, we learned the importance of strategically planning focused interaction activities to ensure increased involvement and prevent redundancy.

Applicability and Future Work

Based on our continuous evaluation results and faculty and department needs, our future plans include creating an asynchronous, fully online version of IDL6543 and adding more media elements to the course. We believe that the valuable information we obtained from this study will not only help us as we continually improve our future course offerings, but also provide instructional designers and administrators of other higher educational institutions with new and reliable tools for designing, delivering, and evaluating faculty development programs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the UCF instructional design team, faculty stakeholders, and CDL executive stakeholders for their efforts and participation in the IDL6543 redesign. We would also like to thank the editors and reviewers for their comments and suggestions to improve the quality and readability of this article.

- Tom Cavanagh, presentation at Center for Distributed Learning Staff All Hands Meeting, University of Central Florida, March 28, 2012.

- Cheryl Amundsen, Philip Abrami, Lynn McAlpine, Cynthia Weston, Marie Krbavac, A. Mundy, and M. Wilson, "The What and Why of Faculty Development in Higher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature," presentation, American Educational Research Association, Faculty Teaching, Development and Evaluation SIG, 2005.

- Baiyun Chen, Dale Voorhees, and Devon Weaver Rein, "Improving Professional Development for Teaching Online," presentation, Edutainment 2006: International conference on E-learning and Game.

- B. J. Eib and Pam Miller, "Faculty Development as Community Building," International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 7, no. 2, 2006, pp. 1–15; Lynn Feist, "Removing Barriers to Professional Development," Transforming Education through Technology Journal, vol. 30, no. 11, 2003, pp. 30–36; and Glen C. Hamilton and James E. Brown, "Faculty Development: What Is Faculty Development? "Academic Emergency Medicine Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, vol. 10, no. 12, 2003, pp. 1334–1336.

- Amundsen et al., "The What and Why of Faculty Development."

- Ibid.

- Larry Johnson, Samantha Adams, and Michele Cummins, The NMC Horizon Report: 2012 Higher Education Edition, The New Media Consortium, 2012.

- Angela van Barneveld, Kimberly Arnold, and John P. Campbell, Analytics in Higher Education: Establishing a Common Language, EDUCAUSE, 2012.

© 2012 Baiyun Chen, Amy Sugar, and Sue Bauer. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article (September/October 2012) is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.