Key Takeaways

- The Ohio State University Libraries created an organizational policy for digital preservation, shared here to address the policy development process and its importance to an organization, and to provide an outline of repeatable best practices.

- By developing and adopting a policy, set of best practices, and standards, a university or library does not need to wait for an out-of-the-box solution, instead taking incremental steps to provide a better digital preservation environment.

- A successfully crafted and adopted digital preservation policy is a major accomplishment — it is an institution/organization putting a stake in the ground or drawing a line in the sand to say, "Digital preservation is important to us."

Daniel W. Noonan is assistant professor and e-records/digital resources archivist, The Ohio State University Libraries University Archives.

Today, when more and more content and data are born digital or converted to digital to enhance access, archives and libraries, researchers, and institutions grapple with providing effective digital preservation to keep this content accessible not just now but well into the future. In 2012, The Ohio State University Libraries (OSUL), with a cross-functional team representing OSUL's institutional repository, information technology unit, and special collections and archives, embarked on a year-long process to develop a digital preservation policy framework. The purpose of the framework is to formalize our "…continuing commitment to the long-term stewardship, preservation of, and sustainable access to [the library's] diverse and extensive range of digital assets."1

A lot has been written about digital preservation and accompanying models, from the Digital Preservation Three-Legged Stool2 to OAIS3 to the Data Curation Lifecycle4 and the Records Continuum,5 among others; guidelines from NEDCC's Handbook for Digital Projects6 to the Digital Preservation Management Workshops and Tutorial to North Carolina's Digital Preservation Best Practices and Guidelines; and standards, such as the Library of Congress' Sustainability of Digital Formats Planning for Library of Congress Collections. However, this article intends to use OSUL's experience in creating an organizational policy for digital preservation to address the policy development process and its importance to an organization, and to provide an outline of repeatable best practices, not just for library and archives but also for other institutions and organizations that need to preserve and provide access to digital data, information, and objects.

What Is Digital Preservation?

Digital preservation can be defined as the combination of policies, strategies and actions to ensure access to and accurate rendering of authenticated reformatted and born digital content over time regardless of the challenges of media failure and technological change.7 Graham suggests that for "…the scholarly community to give serious weight to electronic information depends upon its trust in such information being dependably available, with authenticity and integrity maintained."8 To effectively accomplish the activities of digital preservation, an institution or organization should have a digital preservation policy that articulates and institutionalizes its commitment to their preservation strategies and actions.

Historically, archives and libraries have articulated — in policies and procedures — the process for the preservation of the paper-based documents and analog objects within their institutions. As Marcum noted in 1996, "Preservation is a fundamental responsibility of libraries and archives of record. To be sure, the preservation imperative has been imperfectly carried out in the print environment, but the problem grows even more complicated in the digital world."9 Just because the process of digital preservation might be more complicated, does anyone really need a policy for digital preservation separate from their institution's preservation policy for books, manuscripts, and/or physical objects?

There is a fundamental difference in trying to preserve paper-based and/or analog objects and digital objects; the Society of American Archivists' definition for preservation states:

- The professional discipline of protecting materials by minimizing chemical and physical deterioration and damage to minimize the loss of information and to extend the life of cultural property.

- The act of keeping from harm, injury, decay, or destruction, especially through noninvasive treatment.10

This definition infers the preservation of the original artifact or object, whereas the previously defined objective of digital preservation "…is the accurate rendering of authenticated…content over time." By definition, digital preservation does not necessarily guarantee "preservation" of the actual digital artifact or object, but its informational value and how it is rendered and accessed. Consequently, digital preservation is significantly different enough from traditional preservation to warrant a dedicated policy.

With a successful track record for establishing preservation policy for paper-based and analog objects, librarians and archivists have a number of definitive standards to rely on to monitor the effectiveness of the preservation activities for those types of objects. Nevertheless, where does one begin to develop a digital preservation policy? As Peter Lyman asked in 1998, "When we know a book is important, we know what to tell a publisher: print it on acid-free paper. Well what do we do with digital documents?"11

Why Is Policy Important? A Literature Review

Why does an institution or organization need a "policy"? If we first look to the literature about preservation policy, Morrow articulates in Defining the Library Preservation Program that,

The process of developing policy, or the periodic review of an established policy, allows a library to establish and shape an institution-specific context for preservation activities…. The existence of a formal preservation policy statement will make it easier for a library to codify preservation practices and implement preservation activities evenly throughout the various autonomous custodial units that make up most larger libraries…. Finally, the development of an institutional preservation policy reflects the reality that libraries are systems built on standard practices. Standardization is necessary to maintain order and ensure quality and cost-effectiveness; however, unexamined practices lead to entrenchment.12

Lyman and Besser noted, "The long term preservation of information in digital form requires not only technical solutions and new organizational strategies, but also the building of a new culture that values and supports the survival of bits over time."13 Beagrie, Semple, Williams, and Wright reinforced the idea that "…any long-term access and future benefit may be heavily dependent on digital preservation strategies being in place and underpinned by relevant policy and procedures…[and that]…[t]he digital preservation policy should be integrated into business drivers, activities and functions e.g. regulatory compliance, staff development, applied technology, academic excellence."14

The Electronic Resource Preservation and Access Network's (ERPANET) Digital Policy Preservation Tool suggests that "A policy forms the pillar of a programme for digital preservation. It gives general direction for the whole of an organization, and as such it remains on a reasonably high level…. From an external point of view, a written policy is a sign that the organization takes the responsibility to preserve digital material…"15

Cloonan and Sanett noted, "…the lack of preservation policies in place is a distinct gap in the research design of many of the projects and possibly reflects a lack of commitment among the stakeholders in institutions."16

McGovern reported,

Policies and other documentation of decisions and actions represent one of the best indicators of the development of the organizational leg. At the 2006 Best Practices Exchange (BPE) in North Carolina 'participants stressed again and again that a successful digital preservation program requires a strong foundation…. Participants identified four essential elements for building a strong foundation for a digital preservation program: support and buy-in from stakeholders; 'good enough' practices implemented now; collaborations and partnerships; and documentation for policies, procedures, and standards.'17

While McGovern's observation about the sentiments expressed at the 2006 BPE noted that that there is an awareness of the need for documented digital preservation policy, Russell reported in 2007 the results of a survey showing:

The data indicated that although 92 percent of institutions were already digitizing from source materials, only 29 percent had written polices or plans for digitization. While 59 percent of respondents reported that their digital materials had a need life of 25 years or longer, which was the longest option offered in the questionnaire, only 13 percent had written plans or policies for digital preservation. This data suggested that institutional planning for digitization lagged far behind creation and confirmed our view that institutions needed help with policy development…18

The results of two studies — one in Europe and one in North America — published in 2011 indicate that progress has been made, but there is still a gap between preserving digital objects and having articulated policy to govern and manage the process. A 2009 Planets19 project survey showed that:

Nearly half (48%) of the organisations surveyed have a policy for the long-term management of digital information, where long-term is defined as greater than five years. This varies by organisation; 64% of archives, and 43% of libraries, have a digital preservation policy. However, only one-quarter (27%) of government departments, and the public sector in general, have a digital preservation policy in place. A high proportion of commercial organisations (88%), and suppliers and vendors (60%), have digital preservation policies, although these results should be treated with caution, due to the small size (eight commercial organisations, and ten suppliers and vendors), and potentially unrepresentative nature, of the sample.20

Similarly a spring 2010 survey of 72 Association of Research Libraries institutions (ARL is the nonprofit organization of 126 research libraries at comprehensive research institutions in the United States and Canada that share similar research missions, aspirations, and achievements) indicated that 51.5 percent have preservation policies for their institutional repositories.21

Bergin conducted a study in 2013 "…to identify institutions with established digital preservation programs, and investigate how these programs were implemented." Her study, which included responses from 148 institutions, produced very similar results to Russell's, indicating that while over 90 percent of the respondents had undertaken efforts to conduct digital preservation, less than 30 percent had actual written digital preservation policies.22

Ambacher expressed concern that, "Worldwide there is a lack of confidence in the ability of archivists and librarians to manage digital data. Those professions are seen as slow to embrace digital data preservation…. The professions have spent far too much time studying the issues, far too much time on grant-funded pilot projects, far too much time developing redundant best practices, and far too little time developing recommended standards. The professions may have been waiting for someone else to solve the problems, for someone else to provide an out-of-the-box solution."23 However, by developing and adopting a policy, set of best practices, and standards, one does not necessarily need to wait for that out-of-the-box solution, and can begin to take incremental steps to provide a better digital preservation environment.

How Did OSUL Get Here? Journey toward a Digital Preservation Policy

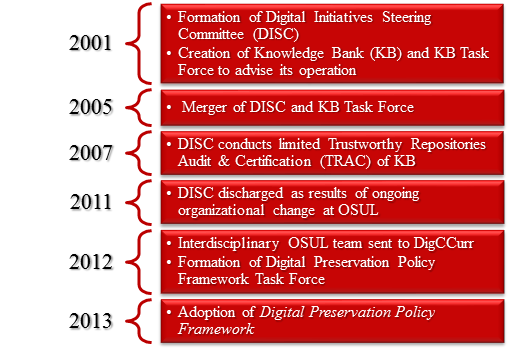

The commitment within OSUL to the development of a digital preservation policy did not occur overnight; it was the culmination of more than 10 years of digital initiative efforts at Ohio State (figure 1). OSUL had been involved in a variety of digital initiatives for more than a decade without an articulated policy in place to guide a consistent approach to managing and preserving those digital assets.

Figure 1. Timeline to Digital Preservation Policy Framework

In late 2001, the recommendations from the OSUL Digital Projects Task Force suggested that line staff be dedicated to digital initiatives; however, existing personnel and budgetary constraints did not allow for this. Instead, the Digital Initiatives Steering Committee (DISC) was created as a means "…to maintain momentum, solicit, evaluate, and support digital projects…"24 At about the same time Ohio State embarked on a project to create an institutional repository called the Knowledge Bank (KB) that collects, indexes, and preserves digital content produced by faculty and supports the creation of new research content.25 The KB was realized originally as a collaboratively funded effort with the Office of the CIO, managed by OSUL. Initially, OSUL assigned a task force to advise the KB operations that had regular interaction with DISC through 2005 when it was concluded that the projects being coordinated by the two groups overlapped sufficiently to warrant a merger.26

Over the decade of DISC's existence, the group primarily focused its efforts on prioritizing and shepherding digital projects, as well as identifying digital best practices. It also began to focus on the need for digital preservation standards. Two of the three key findings of a 2007 Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification (TRAC)27 review of the KB noted that there was "…insufficient centralized prose documentation for the many activities associated with the KB…[and]…no clearly documented preservation strategy…"28 In other words, OSUL had not articulated a digital preservation policy. Still, it would be another five years before OSUL officially began to construct a digital preservation policy framework.

In the fall of 2011, OSUL officially discharged DISC as part of a larger organizational restructuring. Interestingly, this coincided with now-former DISC members participating in two meetings in the region related to digital preservation.29 The OSUL participants came away from these meetings reinforced in the notion that the libraries needed a written, well-articulated digital preservation policy.

In the spring of 2012, OSUL opted to send a multidisciplinary team to the DigCCurr Professional Institute at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill (UNC), part of the Carolina Digital Curation Curriculum Project. The team was represented by the head of digital content services (which includes management of the institutional repository), a programmer from application development and support, and the digital resources archivist. The DigCCurr Professional Institute is a three-part program that is "…aimed at assisting digital collection managers in developing their digital curation strategies…" and spans a six-month period. It begins with a weeklong intensive institute at UNC; is followed by a six-month period where attendees work at their home institutions on personal projects that they identified during the intensive; and culminates in a two-day meeting at UNC to report on the projects' progress. The OSUL team opted to use their project as a means of developing a digital preservation policy.

What Do You Plan to Do? Proposing a Policy Development Process

Policy development has to be sanctioned at the highest level of an organization, but with buy-in throughout the organization if it is going to be effective. Cloonan and Sanett observed, "We suspect that policy is lagging far behind the development of standards, because the development of good public policy requires the appropriate political climate as well as the cooperation of numerous stakeholders."30

The team assembled by OSUL to attend DigCCurr did benefit from an organizational, political climate that was intent on improving the way in which OSUL managed its digital assets, although there was not a preconceived notion as to what the team's potential project would be. First the project team would need to experience the DigCCurr intensive, then determine what they believed would be the highest priority for OSUL. Finally, they would have to formally propose a project to the OSUL Executive Committee (OSUL Exec), comprised of the libraries' director, associate directors, and assistant director.

In preparing a proposal to OSUL Exec to form a task force to develop a digital preservation policy framework, the project team met several times in June and July of 2012 to debrief and conduct a cursory TRAC review — as a gap analysis — of the libraries' digital initiatives. In addition to identifying technological and resources gaps, it reinforced the more in-depth TRAC review of four years earlier that OSUL had "…no clearly documented preservation strategy…"31 Without having a policy framework or strategy, it is hard to justify the need to fill the technological, resources, and other administrative gaps.

During a meeting at the end of July with representatives of OSUL Exec to make the case for a policy development task force, the team stressed that OSUL was at the second stage of Kenney and McGovern's Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation:

- Acknowledge: Understanding that digital preservation is a local concern;

- Act: Initiating digital preservation projects;

- Consolidate: Seguing from projects to programs;

- Institutionalize: Incorporating the larger environment; and

- Externalize: Embracing inter-institutional collaboration and dependency.

A key component required to move to the third stage is that "…the organization makes explicit its commitment to digital preservation by developing basic, essential policies and by understanding the value of policies as part of the solution…"32

OSUL Exec made that commitment, in mid-August 2012, by creating the Digital Preservation Task Force (DPTF) "…that has evolved out of The Ohio State University Libraries' (OSUL) involvement in the DigCCurr Institute 2012. It is charged with developing a digital preservation policy framework for all OSUL digital assets that will address: Mission statement, Guiding principles, Standards identification and Prioritization process."33 The DPTF consisted of the three DigCCurr Institute attendees, who would consult as necessary with personnel from OSUL units including but not limited to Collections Management, Preservation and Reformatting, Special Collections and Archives, and the Head Digital Initiatives.34

What Is the Plan? The Policy Development Process

The goals of a good policy "…are to provide guidance and authorization on the preservation of digital materials and to ensure the authenticity, reliability and long-term accessibility of them…Moreover, a policy should explain how digital preservation can serve major needs of an institution and state some principles and rules on specific aspects which then lay the basis of implementation."35 The best policy documentation is succinct and to the point, as it should be easily digestible and understandable to everyone throughout an organization. It should address what should be accomplished and why; how it should be done should be a separate set of implementation and/or procedural documents.

How the does an institution or organization move from a blank piece of paper or screen to a robust, articulated policy? The DPTF approached its assignment by conducting a review of a dozen digital preservation policy frameworks for institutions and organizations that ranged from national libraries to academic libraries to one dedicated solely to research data.36 The vast majority of the frameworks analyzed were four to six pages in length. The team's analysis revealed the following common components that constituted a good digital preservation policy:

- Introduction or Purpose: A contextualization and articulation of the need for the policy.

- Mandate: A statement that addresses legal, institutional, and/or unit requirements to preserve digital objects.

- Objectives: A description of the intentions of an institution's or organization's digital preservation program, possibly tied into the organization's mission statement.

- Scope: A statement that establishes boundaries as to what the organization will preserve and more often than not establishes priorities among various materials; examples include but are not limited to born digital, digitized with analog original, digitized without analog original, and commercially available digital materials.

- Challenges: An identification and articulation of the challenges and risks associated with the process of digital preservation.

- Principles: A statement that addresses the values and philosophy by which an organization operates its digital preservation program.

- Roles and Responsibilities: An identification of the various roles in the digital preservation process; it may aggregate the roles at an institutional or unit within an institution level, establish group roles, or identify individual roles.

- Collaboration: A statement that acknowledges that digital preservation is a shared community responsibility and identifies steps to be taken to cooperate and collaborate.

- Selection and Acquisition: Criteria for materials to be preserved, tied to a repository's collection development policy.

- Access and Use: A statement that addresses the concept of open access as well as levels of restriction; further, it addresses the likely inability to render the original digital artifact and that the effort will be made to deliver the best possible surrogate.

- References: A listing that identifies other standards and policies referred to within the policy document.

- Glossary: A listing of terms as necessary.

One standard administrative section that was missing from all but one of the policies reviewed was a statement to maintain the currency of the policy through a regular review process.

While some parts of the policy framework are repeatable almost verbatim from policy to policy (and in OSUL's final policy document), others needed to be considered within the organization's environment. The team identified the pieces of each of the reviewed policies that best fit the OSUL organizational setting — certainly all of those identified above — with additional sections for:

- Categories of commitment: a more detailed articulation of the scope

- Levels of preservation: an articulation of the digital preservation spectrum that moves from safe storage to full information preservation

- Implementation: an acknowledgment that policy implementation is contingent on appropriate resources and additional activities; in other words, just because the policy exists does not mean preservation activity is conducted

- Review cycle

Further, the team added appendices to address a more granular discussion of roles and responsibilities, including the glossary and list of sources consulted.

The DPTF assigned sections of the proposed policy framework to each other to complete initial drafts, and it met regularly throughout September and October to review and revise these drafts. The work was conducted on OSU's CarmenWiki, which allowed for collaborative authoring and versioning as well as providing transparency throughout the process. The team also had the opportunity during this period to meet with its DigCCurr Faculty Mentor, Nancy McGovern, the head of Curation and Preservation Services at MIT Libraries, to discuss its progress and the direction the project was taking.

As noted, many of the policy framework sections were incorporated nearly verbatim from examples the DPTF examined. However, several were significantly modified or wholly new. The Principles section of the policy framework, for example, took on a somewhat different look than many of the policies that the team had reviewed. The DPTF felt that there was a need to not only articulate the guiding principle that OSUL was committed to long-term preservation of its digital assets and that digital preservation is an integral part of its processes, but also to establish a set of operating principles and commit to an adherence to standards. The Operating Principles are aspirational and state that the library will strive to develop a scalable, reliable, sustainable, and auditable digital preservation infrastructure; comply with OAIS; ensure data integrity; and comply with copyright, intellectual property rights, and other legal rights among other aspirations.37

OSUL Digital Preservation Guiding Principles

OSUL will use consistent criteria for selection and preservation as for other resources in the libraries. Materials selected for digital stewardship and preservation carry with them OSUL's commitment to maintain the materials for as long as needed or desired.

- The libraries are committed to the long-term preservation of selected content.

- Digital preservation is an integral part of OSUL's processes.

- Processes, policies, and the institutional commitment are transparently documented.

- Levels of preservation and time commitments are determined by selectors, curators, in consultation with technical experts.

- OSUL will participate in the development of digital preservation community standards, practice, and solutions.

OSUL Digital Preservation Operating Principles

The library will strive to:

- Develop a scalable, reliable, sustainable, and auditable digital preservation infrastructure

- Manage the hardware, software, and storage media components of the digital preservation function in accordance with environmental standards, quality control specifications, and security requirements

- Comply with the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) and other appropriate digital preservation standards and practices

- Ensure that the digital archive is as interoperable as possible by utilizing open-source options whenever feasible

- Ensure the integrity of the data

- Secure metadata (e.g. administrative, descriptive, preservation, provenance, rights, and technical) necessary for the use of the digital assets

- Comply with copyright, intellectual property rights, and/or other legal rights related to copying, storage, modification, and use of digital resources

OSUL Digital Preservation Standards

- Ohio State is best served when distributed and disparate systems conform to standards and best practices that make communication between these storage systems possible.

- To utilize the OAIS Reference Model as the basis for developing and implementing strategies and tools for long-term digital information preservation and access.

When the DPTF presented the draft policy framework to the OSUL Exec for sponsors in mid-November, it was generally well received. However, the Categories of Commitment section was a point of contention and a lesson learned in how the structural presentation of information carries certain biases. In the initial draft the sponsors reviewed, the section was listed as Commitments with subcategories for Priorities and Levels of Preservation. The priorities appeared, without an introductory statement, as a numbered list:

- Born-digital materials

- Digitized materials (no available analog)

- Digitized materials (available analog)

- Commercially available digital resources

- Other items and materials

The DPTF believed that if OSUL could establish an effective process for preserving born-digital assets, it would benefit all the other categories in the list. Further, the team felt that born-digital and digitized materials with no analog copy available were inherently more at risk and therefore a higher priority. However, one can also look at that list without a contextualizing statement and presume that the number one priority for OSUL as an organization is to preserve its digital assets, not the books on the shelves.

Therefore, the title was changed to Categories of Commitment, the subcategory title Priorities was dropped, an introductory statement was added, and the numbered list was changed to a bulleted list. Subsequently, the Levels of Preservation subcategory was elevated to a category of its own.

OSUL Digital Preservation Categories of Commitment

OSUL's levels of commitment as outlined below recognize that developing solutions for "born digital" materials informs solutions for the other categories; it does not imply that these assets are inherently more valuable or important than any of the other categories and/or our traditional, analog materials.

- Born digital materials: Rigorous effort will be made to ensure preservation in perpetuity of material selected for preservation, both library resources and institutional records.

- Digitized materials (no available analog): Every reasonable step will be taken to preserve materials without a print analog, when re-digitizing is not possible or no analog versions are located elsewhere. Also included are digitized materials that have annotations or other value-added features making them difficult or impossible to recreate.

- Digitized materials (available analog): Reasonable measures will be taken to extend the life of the digital objects with a readily available print analog. However, the cost of re-digitizing as needed will be weighed against the cost of preserving the existing digital objects.

- Commercially available digital resources: OSUL has responsibility for working externally through consortia, licensing agreements, etc. OSUL will assure that one or more parties provide the necessary infrastructure for preservation activities, so that Ohio State faculty, staff, and students will have adequate ongoing access to commercially available digital resources. If the resources are external to OSUL, there needs to be an articulated exit strategy in the event of the cessation of the consortia or licensing agreements. Particular emphasis should be given to resources that exist in digital form only.

- Other items and materials: No preservation steps will be taken for materials requested for short-term use such as materials scanned for e-reserve and document delivery, or for content that is deemed unessential.

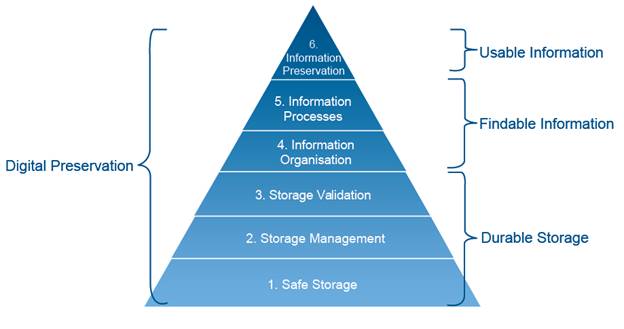

The Levels of Preservation identify the spectrum of preservation activities from safe storage and bit preservation to full information preservation. Although the DPFT originally construed this as a means of identifying OSUL's commitment to preservation at a point along that spectrum, ultimately the team decided that this section needed to stand alone as its own foundational statement and aspirational goal. In deciding on a model to describe the levels of preservation, the DPTF reviewed two models, the National Digital Stewardship Alliance's (NDSA) Levels of Preservation and Preservica's (previously Tessella Technology and Consulting) Digital Archiving Maturity Model.

The NDSA's Levels of Preservation is a matrix model that addresses storage and geographic location, file fixity and data integrity, information security, metadata, and file formats along a four-level spectrum, from protecting the data, knowing the data, monitoring the data, and repairing the data.38 Preservica's Digital Archiving Maturity Model (see figure 2) is a pyramidal model that moves through six stages from safe storage to information preservation. The first three levels are about durable storage and creating an environment in which the objects are preserved. The final three levels are meant to ensure the intellectual access to and use of the objects.39 In choosing to include Preservica's model in the policy framework, DPTF recognized that it more suitably describes the conceptual process of digital preservation, whereas NDSA's model serves as a more effective, actionable tool for implementing digital preservation. As such, the team placed the NDSA matrix in a "parking lot" for future consideration as part of implementing a digital preservation program within OSUL.

© 2014 Preservica. All rights reserved.

Figure 2. Preservica's Digital Preservation Maturity Model

The Roles and Responsibilities section in the policy frameworks that the DPTF reviewed varied from generic statements to an itemized list of functional roles. Unlike most policy frameworks OSUL's framework ties the roles to — and adapted the language from — those specified in the OAIS Reference Model.40 The roles include producers, management, administrators, cooperating archives, consumers, and user groups/client groups. Additionally, the team created an appendix that further identifies specific administrator roles and responsibilities tied to OSUL positions. As such, the appendix can be modified without having to change the policy when there are organizational changes.

OSUL Digital Preservation Policy Framework Roles and Responsibilities

OSUL has identified the following stakeholder categories for the digital preservation program. The terminology is adapted from the OAIS Reference Model (CCSDS 650.0-M-2 (2012)).

- Producer: The role played by those persons or client systems that provide the information to be preserved. Producers include faculty, students, staff, alumni, collectors, creators of content, publishers, and others.

- Management: The role played by those who set overall OAIS policy as one component in a broader policy domain, for example as part of a larger organization.

- Administrators: Content stewards (designated staff responsible for selection and for ongoing curation of specific collections), digital preservation specialists and working teams (see appendix for list). Administrators will be responsible for the establishment of the digital preservation program and for day-to-day management of the digital archive(s).

- Cooperating Archives: OAIS definition — Those archives that have designated communities with related interests. At OSUL we think of this group as collaborators.

- Consumer: The role played by those persons, or client systems, who interact with OAIS services to find preserved information of interest and to access that information in detail.

- User Groups/Client Groups: The various types of clients who use OSUL's digital collections.

Appendix 1: OSUL Administrators in the Digital Preservation Policy Framework

- Collections Strategist

- Electronic Records and Digital Resources Archivist

- Head of Preservation and Reformatting

- Head of Research Services

- Head of the Copyright Resources Center

- Head of Digital Content Services

- Head of Digital Initiatives

- Head, Applications Development and Support

- Systems Administrator and Integration Coordinator

- Curators

- Metadata services staff

- Technical staff

One section that was drafted, but ultimately left out of the policy framework, dealt with defining what a digital master is, as well as creating definitions for various derivative file types. While this is important to better understand and more effectively implement digital preservation processes, the DPTF determined that it was not policy, but the establishment of standards, which is part of the implementation process.

Authority and Buy-in: The Policy Approval Process

Based on the feedback provided by the task force sponsors, the DPTF refined the draft policy framework so that by early January 2013, when two of the task force members attended the DigCCurr follow-up in Chapel Hill, they were able to report on progress of the policy framework development and seek feedback from the cohort and mentors. The progress report was well received and generated useful discussion to assist the team in completing the project. While the policy framework was not yet approved and adopted, and therefore not fully completed within the DigCCurr six-month timeframe, the DigCCurr follow-up meeting allowed the OSUL team to focus on what it would take to complete the project and begin to consider what would be necessary for implementing the framework.

A commitment to complete the policy framework was articulated in a second six-month plan, which included incorporating the feedback gathered at DigCCurr, presenting the draft policy framework to interested parties within OSUL and seeking their feedback, making final revisions to the framework, and presenting it to OSUL Exec for final approval and adoption. Once adopted, there would need to be an awareness campaign to educate OSUL personnel regarding the policy framework. The team recognized that the "awareness" aspect would be the easier part of an implementation plan because it is a human resources issue. Identifying and creating a preservation environment is a hardware, software, monetary, and human resources issue that will take a concerted organizational effort to strategize and implement.

Over the next several months the DPTF members met with groups and individuals within the libraries to disseminate the draft policy framework and seek feedback. Specifically, the team met one-on-one with library personnel who were identified in the Administrators Appendix. This provided fresh insight as several of these individuals were new to OSUL. One administrator's particularly salient observation was that the framework was confusing because it began discussing a program, then shifted into specific policy, and then broadened back out again to talk about a program. This individual asked, "Is the intended purpose of this document to layout [sic] a policy related to the program or to create a program to support digital preservation?"41 In reality, it is neither. Within OSUL, staff view digital preservation as a collection of activities carried out by various programs throughout the libraries, and the policy framework is not meant to be a program blueprint. To set the appropriate tone, the group revised the language:

The primary intention of the digital preservation program is to preserve the intellectual and cultural heritage important to The Ohio State University, while at the same time making sure that it is accessible over time. The program's objectives are to…

to read

The primary purpose of digital stewardship and preservation is to preserve the intellectual and cultural heritage important to The Ohio State University, while at the same time making sure that it is accessible and held in trust for future use. The objectives in this statement define a framework to…

This change facilitates a framework within which the library can holistically approach digital preservation.

When the revisions were completed in June 2013, the final draft was presented to OSUL Exec for consideration and adoption. The policy was approved in August and assigned to the newly formed Strategic Digital Initiatives Working Group (SDIWG)42 for ownership and implementation.

Other Ways to Do It and Lessons Learned

The process OSUL went through to create its Digital Preservation Policy Framework, while successful, is not the only one available to institutions and organization seeking to develop and adopt a digital preservation policy. Several other models can be consulted, including three exemplars:

- Liz Bishoff's "Digital Preservation Plan: Ensuring Long Term Access and Authenticity of Digital Collections" identifies eight components of a good digital preservation plan: rationale for digital preservation, statement of organizational commitment, statement of financial commitment, preservation of authentic resources and quality control, metadata creation, roles and responsibilities, training and education, and monitoring and review.43

- ERPANET's Digital Preservation Policy Tool provides a framework to address the benefits of digital preservation, the scope and objectives of the policy, as well as requirements, roles and responsibilities, context, areas of coverage, costs, monitoring and review, and implementation of the policy.44

- JISC's Digital Preservation Policies Study provides a matrix for policy clauses that include a principle statement, contextual links, preservation objectives, identification of content, procedural accountability, guidance and implementation, a glossary, and version control.45

Table 1 maps the Bishoff, ERPANET, and JISC policy model components to those discovered by the OSUL DPTF in review of existing digital preservation policies from various institutions. The ERPANET Model maps most closely to the policy framework that OSUL adopted.

Table 1. Comparison of policy model components

|

OSUL Review |

Bishoff |

ERPANET |

JISC |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Introduction or Purpose: A contextualization and articulation of the need for the policy. |

Rationale for digital preservation |

Benefits |

Principle statement |

|

Mandate: A statement that addresses legal, institutional, and/or unit requirements to preserve digital objects. |

Rationale for digital preservation |

Requirements |

Contextual links |

|

Objectives: A description of the intentions of an institution's or organization's digital preservation program, possibly tied into the organization's mission statement. |

Statement of organizational commitment |

Scope and Objectives |

Preservation Objectives |

|

Scope: A statement that establishes boundaries as to what the organization will preserve and more often than not establishs priorities amongst various materials; examples include but are not limited to born digital, digitized with analog original, digitized without analog original, and commercially available digital materials. |

Statement of organizational commitment |

Scope and objectives |

Identification of content |

|

Challenges: An identification and articulation of the challenges and risks associated with the process of digital preservation. |

|

Requirements |

|

|

Principles: A statement that addresses the values and philosophy by which an organization operates its digital preservation program. |

Preservation of authentic resources and quality control and metadata creation |

Areas of Coverage |

|

|

Roles and Responsibilities: An identification of the various roles in the digital preservation process; it may aggregate the roles at an institutional or unit within an institution level, establish group roles, or identify individual roles. |

Roles and responsibilities |

Roles and responsibilities |

Procedural accountability |

|

Collaboration: A statement that acknowledges that digital preservation is a shared community responsibility and identifies steps to be taken to cooperate and collaborate. |

|

Context |

|

|

Selection and Acquisition: Criteria for materials to be preserved, tied to a repository's collection development policy. |

|

Areas of Coverage |

Identification of Content |

|

Access and Use: A statement that addresses the concept of open access as well as levels of restriction; further, it addresses the likely inability to render the original digital artifact and that the effort will be made to deliver the best possible surrogate. |

|

Areas of coverage |

|

|

References: A listing that identifies other standards and policies referred to within the policy document. |

|

|

|

|

Glossary: A listing of terms as necessary. |

|

|

Glossary |

|

|

Statement of financial commitment |

Costs |

|

|

|

Training and education |

|

|

|

Review Cycle: Included in OSUL policy, but found in only one policy during our analysis of other policies. |

Monitoring and review |

Monitoring and review |

Version control |

|

Implementation: A statement articulating the commitment to implementing the policy and the need to adopt standards, best practices, and procedures. Included in OSUL policy, but not found during our analysis of other policies. |

|

Implementation of the policy |

Guidance and implementation |

The Bishoff and ERPANET models have sections that specifically address the need for a statement of financial commitment and identification of infrastructure and human resource costs, respectively. OSUL's adopted policy is less direct in its language, addressing it in the Objectives: "The objectives in this statement define a framework to…demonstrate organizational commitment through the identification of sustainable strategies…[and] develop a cost-effective program…" and in the Challenges: "The need for good cost models and affordable programs is widely acknowledged, yet still not fully addressed. OSUL requires sufficient funding for operations and major improvements for digital asset management, as well as designated library funding to sustain ongoing preservation efforts."

One area that the Bishoff model addresses specifically that the OSUL policy framework does not is training. The ERPANET and JISC models both address the need to fund staff training, but do not discuss the need or importance of training in relation to the policy. OSUL initially discussed including a training and awareness campaign as part a more actionable implementation section, but ultimately left that task to the inheritors of the policy, the SDIWG.

Clearly, OSUL benefited from the ability to dedicate three of its personnel to an immersive digital preservation experience, DigCCurr; however, that does not mean that this is the only way to develop and implement a digital preservation policy. Whether an institution or organization — an archive or library, their parent institution, and/or some other subdivision thereof — follows the same path as OSUL, uses one of the above models, or strikes out on its own course, they must recognize that the development of a digital preservation policy is an important exercise that cannot be accomplished overnight. To succeed in developing and adopting a digital preservation policy, OSUL's DPTF found that:

- Before embarking on the drafting of a policy, understand the organization/institution's current environment. Examine the organization/institution through the lens of Kenney and McGovern's Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation and/or TRAC review.

- The process must be sanctioned by the institution's or organization's leadership.

- The policy must be developed at a conceptually high level that addresses what the policy entails and why it is important to the institution/organization, not how it is to be accomplished — that is an implementation matter.

- The policy must be developed with the input of those interested parties who will have to work within the parameters of the policy on a regular basis. Further, an awareness of the variety of biases within an organization is important in crafting the language of the policy so there are few to no misunderstandings. Know your audience and recognize that there may be multiple audiences.

- The development process should be conducted by a multidisciplinary team, as digital preservation is a set of activities conducted by roles that cross many functions and disciplines within an organization. This may be hard for some institutions if all of those roles do not occur within the same organizational hierarchy or simply do not exist.

- The time it will take to accomplish drafting, discussing, revising, meeting with sponsors, meeting with interested parties, revising again, and ultimately adopting the policy should not be underestimated. For many reasons — policy development may not be team members' full-time responsibility or number one priority; the inability to consistently schedule team meetings; the inability to schedule meetings with sponsors or interested parties in a timely manner; unexpected health issues or other emergencies — the process can be delayed.

- Understand that the policy is only part of the organizational leg of a three-legged stool. To implement the policy, the organization/institution needs to also consider the technological infrastructure leg and resources framework leg.

Conclusion

During the policy framework drafting process, OSUL was clearly at Level 1 of the Digital Archiving Maturity Model: "…safe storage — simple bit-level storage…with some level of reassurance that the bits are protected against simple storage failure." While it could be argued that the libraries had bits and pieces of the other five levels, those pieces did not have enough critical mass to warrant saying another level had been attained.

Becker and Rauber suggested that "While policies provide important guidance and set a framework for concrete planning, they do not provide actionable steps for ensuring long-term access…[and should not be confused with]… [a] preservation plan [that] specifies a specific, operational action plan for preserving a certain well-defined set of objects for a given purpose."46 Therefore, in spring 2014 a Masters Object Repository Task Force (MORTF) was "…charged with recommending policies, procedures, and best practices for managing the Libraries' Master Objects Repository (MOR) and related storage services in alignment with the Libraries' strategic plan and other related documents…" including the Digital Preservation Policy Framework document.

The work of the MORTF is intended to help establish an architecture that would begin to more fully address Levels 2 and 3 of the of the Digital Archiving Maturity Model, and begin to move OSUL more fully into the third (Consolidate: Seguing from projects to programs) and fourth (Institutionalize: Incorporating the larger environment) stages of Kenney and McGovern's Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation. It has already addressed an issue that the DPTF put in the "parking lot" — that of defining digital masters. The Master Objects Repository Task Force Report47 is recommending the adoption of a set of standardized definitions for preservation masters, provisional masters, derivative masters, working copies, access copies, and reproduction copies. Further, various workgroups, task forces, and personnel are working on issues of identifying digital preservation formats and workflow standards. Therefore, the Digital Preservation Policy Framework's implementation statement is being realized: "Implementation of this policy framework is contingent upon the infrastructure (technological and human resources) provided by Ohio State and OSUL, the availability of cost-effective solutions, the adoption of standards, and development of best practice and procedures."

A successfully crafted and adopted digital preservation policy is a major accomplishment — it is an institution/organization putting a stake in the ground or drawing a line in the sand to say, "Digital preservation is important to us to be able to manage and provide access to our digital assets into an indefinable future. Further, we are going to conduct the preservation activity in a sound and systematic manner." It provides the framework to begin to develop an effective digital preservation program — but that is a case study for another day.

- The Ohio State University, University Libraries, Digital Preservation Policy Framework (August 2013).

- Originally developed for the Digital Preservation Management workshop at Cornell University in 2003 — and subsequently moved to ICPSR in 2007 and currently maintained by MIT Libraries — the Digital Preservation 3-Legged Stool model addresses (1) organizational Infrastructure, which is expressed in a comprehensive policy framework, providing the rationale and mandate for a program as well as detailing the requisite policies, procedures, and plans; (2) technological infrastructure, which entails preservation planning to provide ongoing support for a robust, flexible, and cost-effective technological platform; and (3) a sustainable resources framework, covering staffing, technological, operational, and other costs, which is necessary to undergird the organizational and technology infrastructures.

- Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model: A high-level model that describes the components and processes necessary for a digital archive, including six distinct functional areas: ingest, archival storage, data management, administration, preservation planning, and access. From Richard Pearce-Moses, A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology, Society of American Archivists, 2005. Full reference model and specifications can be found in Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS), Recommended Practice, CCSDS 650.0-M-2, Magenta Book, Space Communications and Navigation Office, NASA, June 2012.

- The Digital Curation Centre's Data Curation Lifecycle Model "…provides a graphical, high-level overview of the stages required for successful curation and preservation of data from initial conceptualisation or receipt through the iterative curation cycle."

- The records continuum model is alternative to the records lifecycle model where "…there are clearly definable stages in recordkeeping, and creates a sharp distinction between current and historical recordkeeping…[it] sees records passing through stages until they eventually 'die,' except for the 'chosen ones' that are reincarnated as archives. A continuum-based approach suggests integrated time-space dimensions. Records are 'fixed' in time and space from the moment of their creation, but recordkeeping regimes carry them forward and enable their use for multiple purposes by delivering them to people living in different times and spaces." From Sue McKemmish, "Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: A Continuum of Responsibility," Proceedings of the Records Management Association of Australia 14th National Convention, 15-17 Sept 1997, RMAA (Perth, 1997).

- Northeast Document Conservation Center, Handbook for Digital Projects (Massachusetts, 2000).

- Association for Library Collections & Technical Services, "Definitions of Digital Preservation."

- Peter S. Graham, "Issues in Digital Archiving," Preservation: Issues and Planning, Paul N. Banks and Roberta Pilette, eds. (Chicago, IL: American Library Association, 2000), 98.

- Deanna B. Marcum, "The Preservation of Digital Information," The Journal of Academic Librarianship 22, No. 6 (November 1996): 452.

- Richard Pearce-Moses, A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2005).

- Peter Lyman and Howard Besser, "Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory: Background, Current Status, Models for Resolution," Time & Bits Managing Digital Continuity, Margaret MacLean and Ben Davis, eds. (Los Angeles, CA: The J. Paul Getty Trust 1998), 11.

- Carolyn Clark Morrow, "Defining the Library Preservation Program: Policies and Organization," Preservation: Issues and Planning, Paul N. Banks and Roberta Pilette, eds. (Chicago, IL: American Library Association, 2000), 5.

- Lyman and Besser, "Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory," 12.

- Neil Beagrie, Najla Semple, Peter Williams, and Richard Wright, Digital Preservation Policies Study Part 1: Final Report October 2008, A Study Funded by JISC (Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE): October 2008), 5–13.

- ERPANET (Electronic Resource Preservation and Access Network), erpa guidance – Digital Preservation Policy Tool (ERPANET: September 2003), 3.

- Michèle V. Cloonan and Shelby Sanett, "Preservation Strategies for Electronic Records: Where We Are Now—Obliquity and Squint?" The American Archivist 65 (Spring/Summer 2002): 91.

- Nancy Y. McGovern, "A Digital Decade: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going in Digital Preservation?" RLG DigiNews 11, No. 1 (April 15, 2007). McGovern refers to the organizational leg of the digital preservation three-leg stool created for the Digital Preservation Management workshop. Originally developed at Cornell University in 2003, the workshop subsequently moved to ICPSR in 2007 and is currently maintained by MIT Libraries. The three legs of the stool are (1) organizational infrastructure, which is expressed in a comprehensive policy framework, providing the rationale and mandate for a program as well as detailing the requisite policies, procedures, and plans; (2) technological infrastructure, which entails preservation planning to provide ongoing support for a robust, flexible, and cost-effective technological platform; and (3) a sustainable resources framework, covering staffing, technological, operational, and other costs, which is necessary to undergird the organizational and technology infrastructures.

- Ann Russell, "Surveying the Digital Readiness of Institutions," First Monday 12, No. 7 (July 2007).

- Planets, Preservation, and Long-term Access through Networked Services was a four-year project co-funded by the European Union under the Sixth Framework Programme to address core digital preservation challenges. The primary goal for Planets was to build practical services and tools to help ensure long-term access to our digital cultural and scientific assets.

- Pauline Sinclair, James Duckworth, Lewis Jardine, Ann Keen, Robert Sharpe, Clive Billenness, Adam Farquhar, and Jane Humphreys, "Are You Ready? Assessing Whether Organisations Are Prepared for Digital Preservation," The International Journal of Digital Curation 6, No. 1 (2011): 274.

- Yuan Li and Meghan Banach, "Institutional Repositories and Digital Preservation: Assessing Current Practices at Research Libraries," D-Lib Magazine 17, No. 5/6 (May/June 2011).

- Megan Banach Bergin, Sabbatical Report: Summary of Survey Results on Digital Preservation Practices at 148 Institutions (October 2013), 21–22.

- Bruce Ambacher, "Establishing Trust in Digital Repositories," Statistical Science and Interdisciplinary Research Vol. 10: Multimedia Information Extraction and Digital Heritage Preservation, Usha Mujoo Munshi and Bidyut Baran Chaudhuri, eds. (series editor Sankar K. Par) (New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing, 2011), 343.

- Digital Initiatives Steering Committee, The Ohio State University Libraries, Memorandum: Recommendation on the Future of DISC (December 3, 2003).

- Sally A. Rogers, "Developing an Institutional Knowledge Bank at Ohio State University: From Concept to Action Plan," portal: Libraries and the Academy 3, No. 1 (2003): 126.

- The Ohio State University Libraries, Libraries' Digital Initiatives Steering Committee (DISC) Annual Report, (February 2006).

- Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification process is now an ISO standard — Trusted Digital Repository (TDR) Checklist (ISO 16363) — that is based on the OAIS (Open Archives Information System) model and provides tools for audit and certification of the trustworthiness of digital repositories.

- The Ohio State University Libraries, OAIS Working Group (Beth Black, Tschera Connell, Amy McCrory) Trustworthy Repository (TR) evaluation summary, 10/3/2007 (October 2007).

- "Staying on TRAC: Digital Preservation Implications and Solutions for Cultural Heritage Institutions" presented by LYRASSIS (September 27–28, 2011) and "Forever is a Long Time: Preservation Planning for Digital Collections" facilitated by Liz Bishoff for OhioLINK's Digital Preservation Task Force (October 24–25, 2011).

- Cloonan and Sanett, "Preservation Strategies for Electronic Records": 90.

- The Ohio State University Libraries, OAIS Working Group (Beth Black, Tschera Connell, Amy McCrory) Trustworthy Repository (TR) evaluation summary (October 2007).

- Anne R. Kenney and Nancy Y. McGovern, "The Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation," Digital Libraries: A Vision for the 21st Century: A Festschrift in Honor of Wendy Lougee on the Occasion of her Departure from the University of Michigan, Patricia Hodges; Maria Bonn; Mark Sandler; John Price Wilkin (Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2003).

- The Ohio State University Libraries, Digital Preservation Framework Task Forces Charge (August 2012).

- During this effort OSUL was recruiting this newly formed position of head of Digital Initiatives. The individual did not start until April 2013, but was consulted for reactive input prior to the adoption of the policy framework.

- ERPANET, erpa guidance – Digital Preservation Policy Tool, p. 3.

- See "Appendix 3: Sources Consulted" of the Digital Preservation Policy Framework for a listing of institutional policies reviewed.

- The Ohio State University, University Libraries, Digital Preservation Policy Framework (August 2013).

- Trevor Owens, "NDSA Levels of Digital Preservation: Release Candidate One," The Signal, November 20, 2012.

- Preservica, Digital Archiving Maturity Model, white paper (2012).

- Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems, Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Recommended Practice, Issue 2 CCSDS 650.0-M-2 Magenta Book (June 2012).

- Meris Mandernach, "RE: Draft Digital Preservation Policy Framework - input needed" e-mail to Daniel Noonan, Tschera Connell, and Peter Dietz, April 9, 2013.

- The SDIWG [http://library.osu.edu/about/committees/strategic-digital-initiatives-sdiwg] is charged with broad responsibility in crafting the libraries' policies and infrastructure to support the libraries' strategic vision around digital initiatives aligned with the libraries' collections, preservation priorities, and information technology infrastructure. It is chaired by the head of Digital Initiatives. Other members include the heads of Digital Content Services, Thompson Library Special Collections, Application Development and Support, Research Services, and Preservation and Reformatting.

- Liz Bishoff, "Digital Preservation Plan: Ensuring Long Term Access and Authenticity of Digital Collections," Information Standards Quarterly 22, No. 2 (Spring 2010): 21–22.

- ERPANET, erpa guidance – Digital Preservation Policy Tool, 3.

- Neil Beagrie, Najla Semple, Peter Williams, and Richard Wright, Digital Preservation Policies Study Part 1: Final Report October 2008 A Study Funded by JISC, Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), (October 2008), 16–17.

- Christoph Becker and Andreas Rauber, "Decision Criteria in Digital Preservation: What to Measure and How," Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 62, No. 6 (June 2011): 1011.

- The Ohio State University Libraries, Master Objects Repository Task Force Draft (May 2014).

© 2014 Daniel Noonan. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 license.